[Versió catalana] [Versión castellana]

Ignasi Bonet Peitx

Architect

Library Architecture Unit

Library Services Management Unit

Barcelona Provincial Council

1. Introduction: architecture and library

A reflection on the architecture of the contemporary library requires first determining what defines the library at the present time, and the capability of architecture to meet that definition.

1.1 The collection and the library model

The collection of books has been the essential element defining libraries since they first came into being and is implicit in the etymological origin of the word ‘library’ (from the Latin liber, book, and librarium, a place for books; and the Old French librairie, librarie, a collection of books, or bookseller's shop). Thus the library is at the same time a container of books and the building in which they are collected or sold.

The library model has evolved in line with the cultural and economic characteristics of the society of the time. Document mediums, size of collections, social purpose and mission of the institution have evolved, as have the library’s spatial requirements, among many other factors, and the architectural typology of library buildings has evolved accordingly. Throughout history, architecture has responded to the functional and symbolic needs of the moment, perpetuating the protection of collections and the institutional representation role of the library.

1.2 The history of the library: the shift in architectural typologies

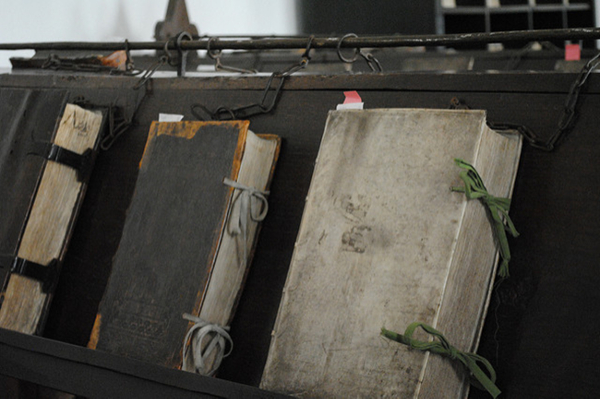

Figure 1. The Librije, Zutphen, the Netherlands (author: Turning Over A New Leaf; licence: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In medieval libraries such as that of Zutphen, in the Netherlands, the large, weighty, parchment books were situated on lecterns facing the scholar’s bench and secured in place by metal chains. Readers positioned themselves in front of the book and turned its heavy but beautiful manuscript pages. The distance from natural light, from the window, could not be too far, so these were small rooms.

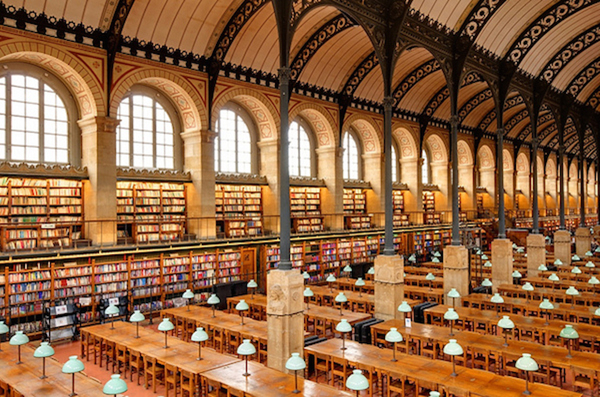

The invention of the printing press led to collections growing considerably, and the introduction of illustration led to the creation of enormous reading rooms, such as that of the Sainte-Geneviève Library in Paris. Designed by the architect Henri Labrouste as a temple of knowledge and space for contemplation, the imposing cast iron structure is studded with huge windows that bestow an air of solemnity on the immense hall, which can seat a large number of readers. Sainte-Geneviève was also the first library to introduce effective separation between the reading room and the document repositories.

Figure 2. Sainte-Geneviève Library, Paris (author: Marie-Lan Nguyen; licence: CC BY 2.0)

Thus we can see that the book format, collection size, user characteristics and the need to symbolically represent the institution, among other factors, define the essential features of the library space. Architecture is the material formalization of this in each case: it provides a response to constructional and functional requirements while enhancing the collective image that embodies the values of the institution. These values were not of course the same in the enlightened thinking of the 19th century as in medieval theocentric society, for example. Architecture responds to everything differently at different historical moments.1

1.3 The contemporary library: digital information and paradigm shift

What is the library like at the beginning of the 21st century? To what extent has the gradual change of the library’s role and transformation of its mission altered the architectural typologies of the buildings that accommodate it?

The digital paradigm has entailed profound social, cultural and economic changes which have redefined the social function of the library, and there is a broad consensus on this new role. In only few cases, however, have the model of library and the architecture that houses it fully embraced the profound transformation of that late 20th-century, post-industrial society into the network society of the 21st century.2

These cases may be few, but they are significant and emblematic. Analysis of the architecture of some of the recent creations that have accommodated the digital paradigm allows us to reach certain conclusions.

2 Digitization and information technologies: from collection-centred space to user-centred space

The emergence of digital information has separated two elements: information itself (the bits of information) has been identified in a way which differentiates it from the physical medium containing it (the printed document). By being digital, information has become intangible and ubiquitous. Besides not being associated with an object, it occupies no space and, since the appearance of the Internet, can be accessible anywhere. Disconnection of information from the physical space the document had traditionally inhabited modifies the spatial requirements of the library and challenges the importance of the collection as it had hitherto been understood.

Furthermore, the assimilation of digital technology, or information technology, has altered the role of the library: “While information technology has not replaced print media, and is not expected to do so in the foreseeable future, it has nonetheless had an astonishing and quite unanticipated impact on the role of the library. […] Rather than threatening the traditional concept of the library, the integration of new information technology has actually become the catalyst that transforms the library into a more vital and critical intellectual center of life...”. (Freeman, 2005)

The digital age has transformed the library’s role. It no longer has to safeguard and preserve the physical collection of objects that contain factual material, but should now also make digital information accessible and enable its use, among other things. In other words, in addition to conserving the collection and ensuring access to it, the library has acquired new roles that emphasise the relevance of users as the end beneficiaries of its activity.

2.1 Sendai Mediatheque

Designed by the architect Toyo Ito and inaugurated in 2001, the Sendai Mediatheque is one of the first projects to demonstrate the new roles of the library. Ito explains the project in the following way: “Up to now, public facilities have been conceived as buildings with clearly defined spaces in which people act in a pre-established manner. […] The sole concern has been to optimize the efficiency of the building, and in doing so it was considered inevitable that restrictions should be imposed on users’ behaviour. But in the street, people behave in a manner which is more free and happy, so why can’t there be more freedom of action in a public building? […] I adopted the barrier-free concept to refer also to freedom with respect to the restraints imposed by the Administration […] to provide a space without barriers”. (Ito, 2001)

Figure 3. Sendai Mediatheque: technological integration (author: Forgemind ArchiMedia; licence: CC BY 2.0)

Thus we can see how users’ freedom had enormous significance in the conception of the building. Their lack of restriction within the library and the fact that they can behave “as if they were in the street” forms part of a strategy to bring the library nearer to the public and make it more open. “Destroy the isolation typical of a conventional library” he would go on to say.

This library’s collection may be found essentially in the reading rooms, but the building’s design grants significant relevance to the spaces where user activity takes place. These are diaphanous, flowing spaces, of uncertain character, that suggest certain flexibility of use and are open to future layout changes. The author speaks of “diffuse architecture”.

The Sendai Mediatheque is one of the first libraries to bring digital technology to the fore and make it the argument of the project, not only for the presence of computers in the rooms to access and employ the information, but also for its constant use of technology to transform spatial perception. “The Mediatheque had to find the way to redefine the library and the art museum [which is also housed in the building] – institutional forms that have remained basically unaltered for a century – through the introduction of new IT resources [...] that the Mediatheque would contribute to transforming current, everyday installations and challenging the preconceived ideas of space and the way it is organized”. (Ito, 2001)

Figure 4. User area, Sendai Mediatheque (author: Yusunkwon; licence: CC BY 2.0)

2.2 Seattle Public Library

The dichotomy between spaces dedicated to the collection and spaces for users becomes more evident in the Seattle Public Library project, designed by the architect Rem Koolhaas and inaugurated in 2004. The text of the Concept book Seattle Public Library proposal is a radical manifesto in favour of transforming the library model: “New libraries don’t reinvent or even modernize the traditional institution; they merely package it in a new way. […] Unless the Library transforms itself wholeheartedly into an information storehouse […] its unquestioned loyalty to the book will undermine the Library’s plausibility at the moment of its potential apotheosis”. (OMA/LMN Architects, 1999)

Figure 5. Seattle Public Library (author: Ignasi Bonet; licence: CC BY 2.0)

The library’s loyalty to the book sacrifices its potential for “aggressively orchestrating the coexistence of all available technologies to collect, condense, distribute, ‘read’ and manipulate information”. (OMA/LMN Architects, 1999)

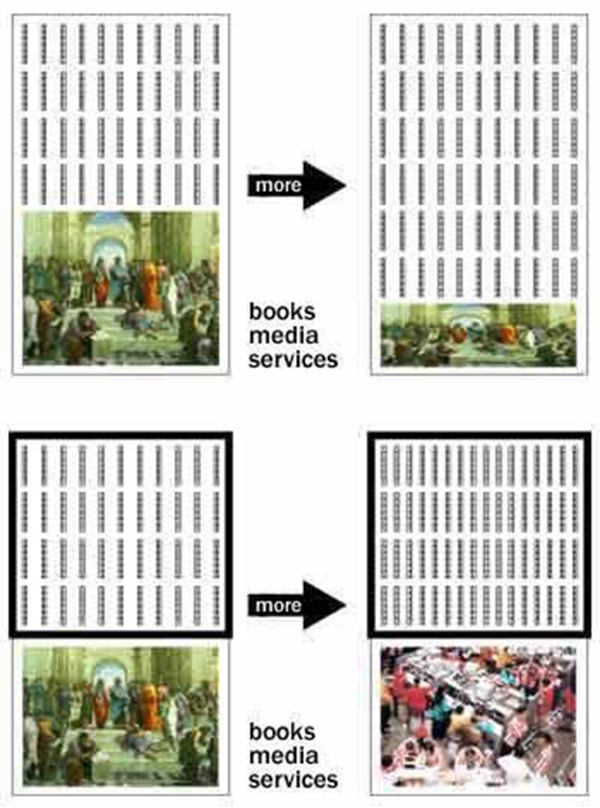

One of the main decisions of this project was to install the collection in an enormous spiral-shaped container, a limited space differentiated from the public areas dedicated to user activities. It was approached from the notion of “compartmentalized flexibility” as opposed to the traditional “uniform flexibility”.

“Flexibility in contemporary libraries has been conceived as the creation of generic floors on which almost any activity can happen. Programs are not separated, rooms or individual spaces not given unique characters. In practice, this means that bookshelves define generous (though nondescript) reading areas on opening day, but through the collection’s relentless expansion, inevitably come to encroach on the public space. Ultimately, in this form of flexibility the library strangles the very attractions that differentiate it from other information resources. Instead of this ambiguous flexibility, the library could cultivate a more refined approach by organizing itself into spatial compartments, each dedicated to, and equipped for, specific duties. Tailored flexibility remains possible within each compartment, but without the thread of any one section hindering or encroaching on the others”. (Kubo; Prat, 2005)

Figure 6. Diagram: compartmentalized flexibility

This approach goes a step further than the Sendai Mediatheque because it overcomes the traditional idea of reading rooms with shelves on which the collection is placed, to integrate as a design strategy the explicit differentiation between the space for holding the collection (the book “spiral”, the store) and the spaces for user activities.

2.3 From collections to access and connections; from shelving to user activities

The principles behind the Sendai Mediatheque and Seattle Public Library reflect the emergence of a new approach to the library space. The area where user activities take place is now the central element and is more important than the collection space, which has taken a back seat since a certain volume of information became digital and accessible online. This is perhaps the clearest evidence of a profound change; the library’s raison d'être is no longer to guarantee the preservation of a documentary collection, but rather to make information available to users so that they might cultivate their own activities (learning, the creation of new contents, leisure, work, reading, socialization, etc.). This change is reflected in the transformation of architectural typologies associated with the library as an institution.

The far-reaching change in the role of the library brought about by the appearance of digital information could have us speaking of a disruptive transformation in that institution’s associated architectural typologies, as occurred with arrival of the printing press. This should be the subject of in-depth study. In this article we limit ourselves to certain evident changes in recent library buildings, in relation to the library’s role in the network society.

3 The role of the library in the network society: guidance for the user

As we said above, broad consensus exists amongst library professionals that, in the network society, the institution that was once an intermediary between authors and readers has become an active agent in the aggregation and dissemination of new documents, as well as in their generation and production.

Hellen Niegaard sums this up in a text from 2009: “At the beginning of the 21st century the concept of the library is shifting in focus: from collections to access and connections; from shelving to user activities with focus on transformation and relations. […] A different library universe is emerging; a new combination of the classic library with its physical materials and the e-library with access to a fast growing number of digitised materials and Internet based services. An important new dimension in relation to the library’s special universe – as a place of knowledge, culture, learning, insight and experience – a development towards experimentarium offering new learning and experiences; a library mediating and displaying both traditional physical formats such as the book and e-materials for download with license agreements with the suppliers. The library has become that ‘third place’ where people want to go either alone or together after home, work or school. In essence, developments and tendencies are stressing the need for reinventing and updating the physical library building.” (Niegaard, 2009)

In the words of Liliane Wong and Nolan Lushington “the many solutions that recent libraries have adopted in redefining their role in this society are indicative of a new spirit. From library shopping centers, library restaurants, libraries without collections, virtual libraries, library community centers, library daycare centers, libraries as acts of redemption to libraries as cultural icons, the pluralism of roles confirms the strength of the institution itself. In this multiplicity of roles the library extends itself further in service of a multi-faceted society, challenging conjectures of its impending obsolescence.” (Lushington, 2016)

3.1 Demands associated with the new role of the library

The emerging demands which are implicit in this new role of the library and which may influence layout of the space and definition of the architecture can be summarized in a few lines:

- Community centre and meeting place, creating a sense of collective identity. Production of events that strengthen the community: lectures and presentations, exhibitions, concerts, receptions, etc.

- Lifelong learning centre, with integration of the new learning paradigms. Importance of autonomous self-learning. Progression from instruction processes to the collective construction of knowledge.

- Production centre of cultural and literary contents, a space for creation. Transition from the read-only culture to the read-write culture, based on Creative Commons licenses that allow copy me/remix me (Lessig, 2008). Appearance of Fab Labs digital manufacturing laboratories.

- Growing importance of collaboration and interaction spaces. Conversation as a basic instrument for collaboration.

- Prioritization of user self-sufficiency and self-service. Integration of technology that enables processes to be automated and redesigned with the user in mind.

- Integration of digital media and services into the library space. Presence of the virtual library and virtual community in the physical space.

- Access centre to information technologies, technological expertise and the fight against the digital divide through information literacy.

- Space of citizen participation and collective empowerment. User participation in designing services and spaces, as well as in decision making. Importance of the systematization of citizen participation processes for collective empowerment.

- Need for spaces for new services and new formats: information services, group-work rooms, silent study rooms, cafés, auditoriums, exhibition halls, multi-purpose rooms, digital audiovisual editing rooms, etc.

- Greater segmentation of the user universe. Specific needs for specific types of users: the young, unemployed, students, enterprisers, minorities, cultural consumers, groups with affinity of interests, etc.

The list could be longer or even restructured because many demands are related; alternatively, it could take the form of a network of related concepts. In any case, we can say that these ideas underlie in general terms the planning processes for new libraries and the strategic reflections on existing facilities.

3.2 Planning and architectural project

In this planning or strategic reflection process every library should define the importance of each of its elements on the basis of their characteristics and context. The public, university, national or specialized library will each place varying degrees of emphasis on each of these elements during the planning stage, until all essential features are brought together in the final project.

The challenge of materializing these goals and aspirations of planners and library managers in the construction project is a significant one, because few examples bear witness to a true melding of the architectural response and the initially presented demands.

In the following sections we focus on a handful of projects whose contribution is relevant in terms of its innovation in the proposed definition of spaces and architectural strategies. This small selection will help illustrate the challenges facing different architectural types associated with each library model and the need to respond to different kinds of change.3

4 The central library in an urban setting: a vast, multifunctional civic storehouse

Despite their monumental grandeur as heirs of the great 19th century institutions, the central public libraries of contemporary capital cities place emphasis on proximity to the public and other less formal aspects. Vast and multifunctional, these civic ‘storehouses’—to borrow Koolhaas’s term—become landmarks that shape urban centrality and broaden their vision of “learning through reading” towards a wide range of programmes focussed on learning in multiple formats on the basis of digital technologies.

We have already referred to the paradigmatic and pioneering case of Seattle Public Library, which in itself would merit a detailed study as regards proposals of new uses and architectural design.4 Also included in this group would be recent projects such as the Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam (Amsterdam Public Library, OBA) by the architect Jo Coenen, inaugurated in 2007, the Library of Birmingham designed by Mecanoo and inaugurated in 2013, and Dokk1 in Aarhus, Denmark, by Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects and open to the public since 2015. We analyse below the Helsinki Central Public Library for the clarity of its functional programme and the innovative uses it proposes, but our observations would also be applicable to the other projects we have mentioned.

4.1 Helsinki Central Public Library

The 2011 functional programme of the future Helsinki Central Public Library is perhaps one of the best blueprints for an urban central library, accompanied as it is by a mission that “enforces learning, skills, personal cultivation and culture as a basis for welfare and competitiveness” with the additional desire to strengthen “user-centred innovative environments and services”. And all this in a project which will become “a cultural centre […] structured around the library and the latest IT media services and would highlight Finnish top expertise”. (The heart…, 2011)

The architectural design competition concluded in 2013, with ALA Architects being the team drawing up the project. The building is currently under construction, with inauguration planned for late 2018. The creation of this facility stands out for the public involvement and participation in defining its services and spaces throughout the entire process.

Figure 7. Rehearsal studio and spaces for creation, Helsinki Central Library (author: Helsinki City Library)

The project includes many innovative spaces that relate to the requirements set out above. The large main lobby will house electronic display boards, self-service automats, a reprographic centre, lounge-type meeting area, a stage for small performances, foyer for the cinema and multipurpose hall and pop-up information points. The event spaces are the cinema, the multipurpose hall, the “Living Lab” and the exhibition hall. The facility also has adjacent public and private services and spaces: café, restaurant and the possibility of a sauna or shops. Like the lobby, the collections area features presentation spaces, projection surfaces and pop-up information points, but also interactive spaces, lounge zones and quiet areas with absolute silence. Especially worthy of note are the spaces for learning and creation. Five clearly differentiated types of spaces are proposed in the “Children’s World” section of the Central Library: informal learning spaces, a virtual world, a quiet space, an adventure space and a fairy-tale corner. The adult spaces for learning and creation consist of workrooms for two people (with prior reservation), individual and group work stations (with laptop hire and personal cupboard), the Fab Lab digital-physical workshop, recording and video studio, the listening, viewing and games room and the teaching, group work and meeting spaces.

Figure 8. Children's area, Helsinki Central Library (author: Helsinki City Library)

The surprisingly comprehensive nature of the project includes a rich diversity of interior spaces, fruit of the multiplicity of services housed in the huge urban containers that are central libraries. However, this diversity of indoor environments is a tendency that could be applicable to all libraries.

Interior variety is the result of a carefully and thoroughly designed functional programme that encompasses all stakeholders and accommodates the full complexity of demands and the maximum number of particularities and requirements for each specific space. The process of reflection necessary to draft such a document is a guarantee of success in the definition of a shared common objective.

We find that this functional programme satisfies point by point all the generic demands described above for contemporary libraries. If the competition’s winning project is anything to go by, reality will confirm this desire.

5 The university library: an opportunity to transform learning environments into more social and collaborative spaces

Information technologies have profoundly transformed learning processes. “What does learning mean when knowledge is abundant and is everywhere?” asks Carlos Magro. The Internet and mobile technology have prompted us to find “new ways of creating and working together” based on the “culture of the open source and collaboration”, so technology not only allows us to do the same as we have always done with greater efficiency, but “above all, gives us a new way of doing things”. (Magro, 2015)

Moreover, the role of the university library has been called into question: “the traditional library we inherit today is not the library of the future. To meet today’s academic needs as well as those in the future, the library must reflect the values, mission and goals of the institution of which it is a part, while also accommodating myriad new information and learning technologies and the ways we access and use them. As an extension of the classroom, library space needs to embody new pedagogies, including collaborative and interactive learning modalities.” This paragraph (Freeman, 2005) sums up the situation of today’s university library very well.

Les Watson understands the learning process as a social construct based on interaction amongst individuals within a conversational framework: “Libraries should provide environments and experiences for learners that enable them to challenge and develop their frameworks of understanding through as rich a variety of conversations as possible”. (Watson, 2013)

These ideas are radically different from the post-industrial university library as we know it. What spatial layout and architectural proposals can respond to this divergence?5

Few university libraries have taken these transformations on board in their entirety, proposing spaces and architecture that are coherent with them. However, two centres stand out for their efforts to do just this: the Saltire Centre in Glasgow and the recently inaugurated Ryerson University Student Learning Centre in Toronto.

5.1 The Saltire Centre

The Saltire Centre at Glasgow Caledonian University was inaugurated in January 2006. It is one of the first university libraries in Europe to include a facility that provides support for conversational learning (the Learning Café) and it offers an innovative approach to the provision of a wide range of environments. These vary from the monastic, which are more conducive to concentration, to the highly interactive.

Les Watson, the project champion who provided the vision and ideas, says that the building, “through its variety of spaces, embraces learner differences and supports a concept of learning as a social process putting human social interaction and conversation at its heart”. Watson also argues that the building also shows “how some current key ideas in educational thinking can influence the learning facilities that we provide.” (Watson, 2007)

Figure 9. Saltire Centre, Glasgow (author: Jisc Infonet; licence: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The guide Designing Spaces for Effective Learning. A guide to 21st century learning space design of JISC (Higher, 2006) explains the ideas behind the project. It speaks of spaces made flexible to accommodate both current pedagogies as well as those that are to come, with a future vision that allows for their rearrangement. These spaces are audacious (with a vision beyond currently available technologies), creative (to transmit energy and inspiration to students and lecturers), supportive (to develop the potential of all students) and innovative (to enable different uses of each space). They are also motivational insofar as they promote collaboration, inclusive personalization and flexibility with regard to technological integration.

There are group-work spaces, café zones, lounge-type areas close to transit routes, “monastic” cells, outdoor terraces and gardens. The layouts of spaces for presentations and group work are easily modified into rows, circles or patterns suiting small groups, with flat-screen terminals and projectors.

Spaces and furniture in the library must be adaptable if they are to “meet the needs not only of its current academic community but also of the community it aspires to create in the future. The principal challenge for the architect is to design a learning and research environment that is transparent and sufficiently flexible to support this evolution in use. […] the library as a place should be self-organizing – that is, sufficiently flexible to meet changing space needs.” (Freeman, 2005)

The Learning Café stands out as a space for group work and social activities, in which coffee and other beverages coincide with conversations and social interaction as essential elements of learning.

The project recognizes the individuality of each student, creating “micro-environments” in response to their wide range of needs and learning styles. In other words, the environmental diversity is due to individual difference, the diversity of needs among different individuals, while at the same time offering students the possibility to choose. Students are encouraged to re-arrange the furniture, in a diaphanous space, so that it meets their needs. There are even semi-private “inflatable igloo” study areas, which are easy to move and re-arrange.

Figure 10. Saltire Centre, Glasgow (author: Les Watson)

Technological integration was a fundamental element of the project: screens, video-conferences, video streaming and interactive whiteboards for visual and interactive learning, wireless technology and USB and audiovisual connections, often built into the furniture. The “technology-rich space” concept (Watson, 2013) to create atmosphere summarizes the adoption of technological integration as a defining element of the library’s interior. “Viewing the library as a technology, as part of the technium that works to increase choice for library users shifts our thinking about technology from operational to user needs. Adopting this strategic stance combines the physical and the virtual, the book and the computer, into a single system of information and learning.”

The acoustic management of spaces, with significant areas of sound-absorbing boards to reduce reverberation time and environmental noise levels, is a key element in maintaining environmental comfort. The use of mobile lamps to gain flexibility in user-control of artificial lighting also provides users with greater control over their environment.

6 The public library: experiential space, third place, retail, interior design and corporate identity

When, in 1999, the Seattle Library Board of Trustees chose Koolhaas’s project, they cited his “intellectual approach to the library of the future”. The space of Seattle Library is continuous rather than fragmented into floors, and the treatment of materials, textures and colours offers a spatial experience that goes far beyond the idea of the traditional library. “There is a kind of sadness about the [traditional] multi-storied-library” said Koolhaas. “It is simply divided into floors and each floor is more or less a random grouping of subjects […] [We wanted to] have a single, continuous experience […]”. (Vivarelli, 2013) The intention is to give users a spatial experience which is interesting and in line with the values of the library (in this case, “the library of the future”).

6.1 The Hjørring Library

This desire to offer experiential spaces with a clear perception of mediation between library materials and the user is present in many contemporary projects.6 The Hjørring Library in Hjørring, Denmark, inaugurated in 2008 on the first floor of the Metropol Shopping Centre, was the result of the conviction that “physical space had to be redefined if it were to complete/supplement the patron’s use of digital and virtual information and experience [of] opportunities”. The materials employed “were mediated much more aggressively, in a more exciting way and in surroundings and contexts that would induce the user to settle down, concentrate, be inspired and tempted. […] First and foremost we saw the library in the shopping centre as what researchers call ‘the third place’ – the place that is not home and not work, but a meeting place, the square in the free space where one goes to watch, to be seen, to experience, learn, play and ‘be’.” (Søndergård, 2010)

Figure 11. Hjørring Library, Hjørring, Denmark (author: Jenniferjoan; licence: CC BY 2.0)

6.2 Third place and retail strategy

The library as a third place has been analysed by many authors. The institution undeniably makes a public space available which is safe, welcoming, open and accessible, where visitors can pass time with friends, recharge the mobile while surfing the Web using the Wi-Fi, or just take a break from work or study. However, unlike many other third places (such as shopping centres, airports or Starbucks cafés) the product the public library offers its customers is completely free. But it is nonetheless a product, as Aat Vos argues in his text Library Refurbishment (Vos, 2016) and in the book 3rd4all - How to Create A Relevant Public Space. (Vos, 2017)

The marketing strategy to sell a product at the retail level (or to lend a book, in the case of the library) is based on a studied process of drawing the customer closer to the product. (In the first place, creating an interest to enter the space; in second place, introducing a change in rhythm which allows for a predisposition and openness to the products on offer; thirdly, a distinction between the different departments or environments that differentiate products according to the specific interests of each customer; and finally, direct interaction with the product). If the library is to be the intermediary between user and book it must attract the attention of the former to the latter, and it must do so through strategies prior to the encounter with the book, strategies such as visual identity and interior design.

6.3 Visual identity and interior design

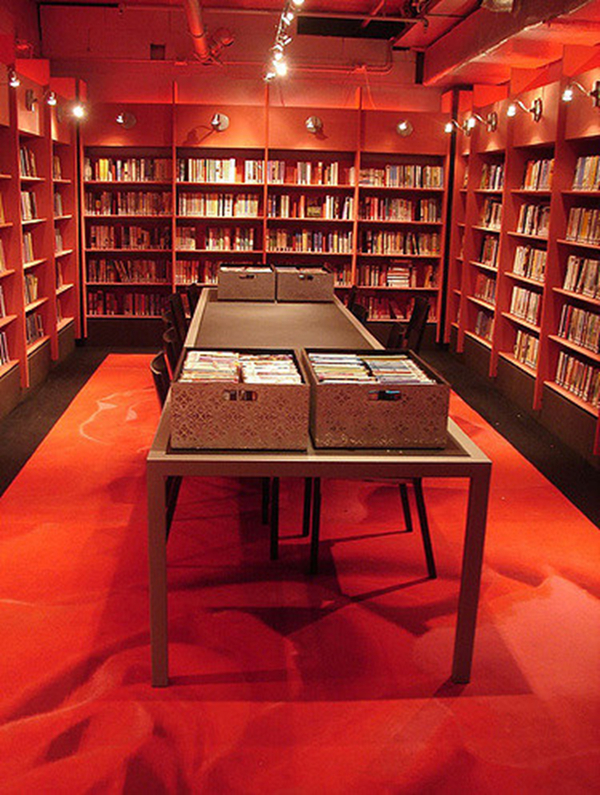

“The traditional library interior usually has a consistently designed atmosphere, with one type of floor covering, a balanced color scheme and a lighting design throughout the entire space. When a library is to be refurbished, one might consider refitting this palette with just the latest materials and fresh colors […] [to achieve] a more differentiated library interior design. One of the main prerequisites is communication. […] When a refurbishment is also used to change the way the collection is segmented, and various departments are introduced, the need for a distinguished look and feel might emerge. It is clear that a differentiation by color, texture or lighting helps to communicate different departments.” (Vos, 2016)

The interior design of the library forms part of the institution’s visual identity and communication strategy and ensures that the user will associate certain values, ideas or feelings with each of the interior spaces and products on display. The conscious use of this strategy when designing the different spaces allows the user’s perception to fall in line with that being communicated by segmentation of the universe of users and the universe of the collection.

These approaches are also relevant in newly-created libraries, as demonstrated by Peckham Library and Media Centre in London (Lushington, 2016), the DOK Library in Delft, Schiphol Airport Library (Vivarelli, 2013) and the Idea Stores in England.

Figure 12. DOK Library, Delft (author: Jenny Levine; licence: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

6.4 Idea Stores

The marketing strategy employed to get the product to the customer, or the book to the user, is particularly interesting in those instances where the aim is to reach out to non-readers. This is the case with the Idea Stores in London, established in the borough of Tower Hamlets. By the year 2000, use of the public library in this district had diminished drastically and reports indicated that a radically different approach to the provision of a public library service was needed. The Idea Store Whitechapel was inaugurated in 2005, and several more have been opened since. (https://www.ideastore.co.uk/)

A few years earlier, the Idea Stores proposal had been presented (Wills, 2004) as an innovative facility to attract new users to the public library and strengthen adult education. It was designed with a style that did not resemble other municipal buildings, looking more like a shopping centre and following retail principles, with the emphasis on independent access and self-service in an easily accessible building. Taking the findings of a market research study into account, it was decided to offer long opening hours and proximity to commercial zones to facilitate users’ access when they were doing their general shopping. The strategy fully accepted that the library’s offer of leisure and culture would compete with the practice of sport and consumption of cinema, cafés and restaurants, or even shopping. So a user-friendly, customer-centred service was defined, aimed at providing a response to local needs.

Figure 13. Image 12. Idea Store Canary Wharf, London (author: Idea Store Tower Hamlet; licence: CC BY-NC 2.0)

Design of the space had to be based on consideration that the facility’s image, or “physical interface”, should foster user loyalty. A brand strategy was developed which included a naming process, and a visual identity was defined. At the same time, a service model and set of values that the building had to transmit were outlined, with the idea that architecture should be at the service of the institution, rather than vice versa. A team of designers also laid down design guidelines that would govern actions in other facilities planned for the borough, each strategically situated in shopping centres.

The criteria for defining the model and spaces included eliminating any barrier that would limit access, programming cultural and training activities, and thinking “retail” rather than “library” (display systems, screens, video wall, etc.); it also prioritized flexibility and adaptability (refurbishment of the interior every three years was planned to maintain the “fresh” look), and self-service, which had to be supported by a clear and direct signposting system which made use of large windows and transparent panels and minimized the need for information desks.

Redefinition of the model also affected the team, the organization’s human capital, which is its most important asset. In line with the motto the customer is king, the way of offering the service was redefined: staff were encouraged to walk around the aisles and attend to users, helping and encouraging conversation. Staff recruitment was based on skills related to empathy.

The pictures of Idea Stores like Idea Store Watney Market or Idea Store Bow (https://www.ideastore.co.uk/idea-stores) clearly illustrate this model of facility and of the architectural response in which it is materialized, which bears little resemblance to the library of the late 20th century’s post-industrial society.

7 Conclusion

The transformation of the library’s role in the network society has led to the redefinition of its mission and the adoption of new architectural design strategies.

The digitization of library holdings has meant that institutions can change their focus from maintaining and conserving of collections to providing a service which ensures that users find information and employ it to gain access to knowledge. The integration of digital technology has significantly modified the processes of acquiring knowledge and learning, as well as the ways we consume culture and leisure.

These changes reflect the greater value that is being given to interaction between users and to the function of conversation as a social act that can support access to knowledge, together with the use of audiovisual mediums and formats. The library becomes a social and community centre, a generator of collective identity and at the same time a producer of new contents and information products.

Embracing these changes has led to innovative library architecture that prioritizes spaces for user activities over spaces for housing physical collections. Areas where users read, contemplate, study, work, listen to media or simply chat and laugh, among other things, are used to support a wide range of activities that enrich the interior of the library building.

Uncertainty over future technological changes requires a greater flexibility of spaces, with proposals for open, “landscape” type areas with mobile fittings and furnishings that can be re-arranged along with their integrated technical installation. At the same time, compartmentalized spaces should be defined for more specific activities (group-work rooms, small auditoriums for presentations, digital creation laboratories, etc.), with highly specific technical and environmental requirements (lighting, acoustics, audiovisual equipment, and so on).

This affects all types of library in a similar way, but in each case some aspects are more relevant than others.

Thus the large, central public libraries become emblematic, multifunctional storehouses, generators of urban centrality, dynamic poles of the city’s cultural life, with a broad offering of services that embraces areas hitherto unheard of in libraries: from digital manufacturing laboratories to restaurants and from small-group workrooms and rehearsal studios to spaces for concerts and huge lobbies bustling with activity.

Transformation of the education paradigm in the 21st century converts university libraries into dynamic, diverse centres of learning with spaces that allow everything from absolute silence and concentration to informal conversational learning processes, encompassing audiovisual technologies and mobile devices with permanent connectivity to the network. This metamorphosis includes the appearance of “micro-environments” with specific technical demands and features (acoustic absorption, user-managed lighting, connectivity, etc.), and the “landscape” office, chaotic and with a layout that users can reorganise to suit their activity.

Public libraries compete in the production of cultural and leisure services with an extensive offering that spans from sport and cinema to restaurants and shopping. Competition in what has come to be known as the “experience economy” draws on the segmentation of services, collections and interior spaces to attract users through a well-defined visual and corporate identity in which the value of interior design should not be underestimated. Marketing techniques usually reserved for retail are applied, entailing a diversification of atmospheres or interior environments that adapt to the values and expectations of each type of user.

In short, as a consequence of information digitization not only has the future of libraries been assured, but they have actually taken on a new cultural and social relevance. This new role involves redefinition of the architecture we once knew, typical of the late 20th century’s post-industrial society, into more changeable and complex typologies. These apparently offer a response to the requisites of the first decades of the 21st century, but will be put to the test by permanent change which may well be what most characterizes the future network society.

Bibliography

Anglada, Lluís; Balagué, Santi (2016). “From Room for Books to Room for Users: An Old Infantry Barracks Meets the Challenge”. In: Joseph Hafner, Diane Koen [eds.] Space and collections earning their keep: transformation, technologies, retooling. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur. ISBN 9783110461978 3110461978.

Castells, Manuel (ed.) (2006). La Sociedad red: una visión global. Madrid: Alianza. ISBN 8420647845.

Freeman, Geoffrey T. (2005). Library as Place: Rethinking Roles, Rethinking Space. Washington: Council on Library and Information Resources, p. 1-9. ISBN 9781932326130.

The heart of the metropolis. Helsinki Central Library architectural competition. 2012-2013. Competition programme (2011) <http://competition.keskustakirjasto.fi/competition-documents/> [Last accessed: 11/04/2017].

Higher Education Funding Council for England, HEFCE / JISC (2006). Designing Spaces for Effective Learning. A guide to 21st century learning space design. <http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140702233839/

http://jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/learningspaces.pdf> [Last accessed: 11/04/2017].

Ito, Toyo (2001). “Lliçons de la Mediateca de Sendai = Leçons de la Mèdiathèque de Sendai”. Quaderns, number 231 (October), p. 134-145. Available at: <http://raco.cat/index.php/QuadernsArquitecturaUrbanisme/article/view/

236738/337548> [Last accessed: 28/01/2017].

Kleefisch-Jobst, Ursula (2016). “On the typology of the library”. In: Wolfgang Rudorf, Nolan Lushington, Liliane Wong. A design manual. Libraries. Birkhäuser, p. 22-29. ISBN 9783034608275.

Kubo, Michael; Prat, Ramon (eds.) (2005). Seattle Public Library: OMA/LMN. Barcelona: Actar. ISBN 8495951630.

Lessig, Lawrence (2008). Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 9781594201721.

Lushington, Nolan (2016). “Public Libraries in the United States”. In: Nolan Lushington, Wolfgang Rudorf, Liliane Wong. A design manual. Libraries. Birkhäuser, p. 38-43. ISBN 9783034608275.

Lushington, Nolan; Rudorf, Wolfgang; Wong, Liliane (2016). A design manual. Libraries. Birkhäuser.

ISBN 9783034608275.

Magro, Carlos (2015). La biblioteca por venir. Soñar el futuro, construir el presente. <https://www.slideshare.net/

carlosmagro/la-biblioteca-por-venir-soando-el-futuro-construyendo-el-presente> [Last accessed: 30/03/2017].

Muñoz Cosme, Alfonso (2004). Los espacios del saber. Historia de la arquitectura de las bibliotecas.

Gijón: Ediciones Trea. ISBN 84-9704-102-X.

Niegaard, Hellen (2009). “Something is changing in the State of Denmark. Six aspects of current Danish library development”. In: Hellen Niegaard, Jens Lauridsen, Knud Schulz. Library space: inspiration forbuildings and design. Danish Library Association. ISBN 9788790849559.

OMA/LMN Architects (1999). “Concept book. Seattle Public Library proposal”. <http://www.spl.org/prebuilt/

cen_conceptbook/page2.htm> [Last accessed: 28/01/2017].

Schmitz, Karl-Heinz (2016). “Form and function in library design”. In: Nolan Lushington, Wolfgang Rudorf, Liliane Wong. A design manual. Libraries. Birkhäuser, p. 30-37. ISBN 9783034608275.

Søndergård, Børge (2010). “New spaces for new uses”. A: Els futurs de la biblioteca pública. Barcelona. <https://elsfutursdelabibliotecapublica.wordpress.com/documentacio/new-spaces-s%c3%b8ndergard/>

[Last accessed: 28/01/2017].

Vivarelli, Maurizio (2013). Lo spazio della biblioteca : culture e pratiche del progetto tra architettura e biblioteconomia. Milano: Editrice Bibliografica. ISBN 9788870757484.

Vos, Aat (2016).“Library refurbishment”. In: Nolan Lushington, Wolfgang Rudorf, Liliane Wong. A design manual. Libraries. Birkhäuser, p. 96-101. ISBN 9783034608275.

Vos, Aat (2017). 3rd4all - How to Create A Relevant Public Space. Rotterdam: NAI Publishers. ISBN 9462083517.

Watson, Les (2007). “Building the Future of Learning”. European Journal of Education, vol. 42, no. 2, p. 255-263.

Watson, Les (ed.) (2013). Better Library and Learning Space. Projects, trends and ideas. London: Facet Publishing. ISBN 9781856047630.

Wills, Heather (2004). “An innovative approach to reaching the non-learning public: the new Idea Store in London”. In: Marie-Françoise Bisbrouck [et al.] [eds.]. Libraries as places: buildings for the 21st century: proceedings of the Thirteenth Seminar of IFLA's Library Buildings and Equipment Section together with IFLA's Public Libraries Section, Paris, France, 28 July-1 August, 2003. München : K.G. Saur. ISBN 3598218397.

Worpole, Ken (2013). Contemporary library architecture: a planning and design guide. London; New York : Routledge. ISBN 9780415592291.

Notes

1 For a brief historical review of the changing trends in library architecture, see “On the Typology of the Library” (Kleefisch-Jobst, 2016), “Form and Function in Library Design” (Schmitz, 2016) and “Public Libraries in the United States” (Lushington, 2016). For a more detailed study, see Los espacios del saber. Historia de la arquitectura de las bibliotecas (Muñoz, 2004).

2 To understand the magnitude of the paradigmatic shift that is occurring in technology, production, economics, culture and society in general as a result of the network society represents, see Manuel Castells’s La sociedad red: una visión global (Castells, 2006).

3 For an introduction to the characteristics of these different types of library see the chapters “National Libraries”, “Large Public Libraries”, “Small Public Libraries” and “University Libraries” in Libraries: A Design Manual (Lushington; Rudolf; Wong, 2016).

4 The quality and magnitude of the project behind the Seattle Public Library merit much more detailed attention than could be given here.

5 The problem facing the current university library goes beyond this aspect of the transformation of learning processes. It is essential, for example, to guarantee access to the immense collections of printed materials by making their management viable and, at the same time, ensuring space for users. This sometimes involves recurring to automated repositories like the Joe and Rika Mansueto Library in Chicago, or off-site cooperative storage facilities like the GEPA (Guaranteed Space for the Preservation of Access) in Lleida (Anglada, 2016). Other factors also clearly condition the management of university libraries, such as the need to integrate physical and digital collections; for reasons of space, however, in this article we have limited our study to those elements that may prove more relevant in redefining library spaces and architecture.

6 During the 1980s and 1990s various authors spoke of the experiential aspects of consumption or the experience society, prior to the appearance of the concept of the experience economy, a term which was coined in 1998 by Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore. This term describes the idea that companies should orchestrate memorable events for their customers, so that the memory in itself—the “experience” —becomes the product. It seems that these ideas from the business world have also reached library management.

similar articles in BiD

- From enshrinement to dematerialization : the progress of library architecture during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries XX al XXI. Gil Solés, Daniel. (2017)

- Documentary legacy from a gender perspective : equality, diversity and inclusion. Perpinyà i Morera, Remei. (2020)

- Del procés de tria a la prescripció de lectures literàries a la biblioteca. Almeida, Patrícia de. (2019)

- Evolución de la biblioteca del Tecnológico de Monterrey, Campus Monterrey. Maya Ortega, Yolanda. (2019)

similar articles in Temària

- Bibliotecas para un tiempo de crisis : edificio y personal. Fuentes Romero, Juan José. (2012)

- L'arquitectura de biblioteques en el segle xxi. Muñoz Cosme, Alfonso. (2011)

- Reflexions japoneses al voltant de l'arquitectura de les biblioteques. Gil Solés, Daniel. (2005)

- El estanque y el río. Arana Palacios, Jesús. (1999)

- El disseny arquitectònic de serveis d'informació. Darder, Jordi. (1992)

Temària's articles of the same author(s)

Bonet Peitx, Ignasi[ more information ]

Creative Commons licence (

Creative Commons licence (