Tuula Haavisto

Library Director

Helsinki City Library

Pirjo Lipasti

Lead Planner

Helsinki City Library

Antti Sauli

Information Services Consultant

Helsinki City Library

Abstract

This paper looks at Helsinki’s new city library, the Helsinki Central Library Oodi, which was launched by the Finnish Ministry of Culture in 1998 and will be opening its doors in December 2018. Located in the heart of the city opposite Parliament House, the Library has become one of the flagship projects celebrating the centenary of Finland's independence. This paper focuses on the practices of citizen participation which have been key in the planning of the Library since its very beginnings, and considers how including the citizens and library users in planning the Library’s new services and functions has promoted grass roots democracy, openness, and a feeling of ownership of the new library.

Resum

Aquest article presenta el projecte de la nova Biblioteca Central de la Xarxa de Biblioteques Municipals d’Hèlsinki. La iniciativa per construir aquest edifici nou va néixer del ministre de Cultura de Finlàndia el 1998, i la nova Biblioteca Central d’Hèlsinki obrirà les portes el desembre del 2018. S’ha triat com un dels projectes principals dels actes de celebració del centenari de la independència de Finlàndia, i estarà situada al centre mateix de la ciutat, davant del Parlament. Aquest article descriu les pràctiques participatives dels processos de planificació de la Biblioteca Central, ja que la planificació participativa ha estat un element clau al llarg de tot el projecte des d’un bon començament. Es va pensar d’incloure la ciutadania i els usuaris de la biblioteca en la planificació dels nous serveis i funcions de la biblioteca, per tal de promoure les bases democràtiques, l’obertura i la sensació compartida de pertinença a la nova biblioteca.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta el proyecto de la nueva Biblioteca Central de la Red de Bibliotecas Municipales de Helsinki. La iniciativa para construir este nuevo edificio surgió del ministro de Cultura de Finlandia en 1998, y la nueva Biblioteca Central de Helsinki abrirá sus puertas en diciembre de 2018. Se ha elegido como uno de los proyectos principales de los actos de celebración del centenario de la independencia de Finlandia, y estará situada en el centro mismo de la ciudad, frente al Parlamento. Este artículo describe las prácticas participativas de los procesos de planificación de la Biblioteca Central, ya que la planificación participativa ha sido un elemento clave a lo largo de todo el proyecto desde un principio. Se pensó incluir la ciudadanía y los usuarios de la biblioteca en la planificación de los nuevos servicios y funciones de la biblioteca, para promover las bases democráticas, la apertura y la sensación compartida de pertenencia a la nueva biblioteca.

1 Introduction

The new Helsinki Central Library will be opened in December 2018 in the very centrum of the city. It will be an important point in the history of a dream-come-true, shared by both citizens, library professionals and politicians. The final City Council decision in January 2015, to realize the building was nearly unanimous. How was that possible, knowing how hard it usually is to decide on building a new expensive public building? At least the politicians know that Helsinki people in general are in favour for the project. Along the whole planning process, citizens had been actively involved and heard. On the other hand, politicians also recognize the need of this kind of public space in city centrums.

2 Background

Public libraries have a special significance for the Finnish people. Libraries are loved and well used across the country which translates into notably high usage numbers (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2012) in comparison with international standards (Libraries.fi, 2016) making library services the most used culture service in the country (Sokka et al., 2014, pp. 20-21). Citizens' favourable attitude towards public libraries reflects also to the public discussion on the Central Library since there has been barely any opposition to the project over the course of the planning process, nor strictures against the building itself after the announcement of the architecture competition winner.

The favourable public opinion of libraries is also widely shared by the Finnish decision makers. From early on the Central Library project has had eminent support as the initiative for the new Central Library building came originally from then Minister of Culture Claes Andersson in 1998 (Central Library Project, 2015). Later, in 2013, Culture Minister of that time Paavo Arhinmäki declared the Central Library as one of the headline projects of Finland's independence's 100th jubilee (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2013). By including the Central Library as a headline project of Finnish independence's centenary anniversary year, the government also committed the state to take part in funding the project.

As well as general support of the public there is also a genuine need for public space for citizens in the city centre area. University of Helsinki opened a new main library in the city centre in 2012. The university's main library Kaisa House was originally planned to facilitate 5000 visitors daily but proved soon to be much more popular than expected. The building's daily usages peaks now at over 9000 (Helsinki University Library, 2016) visits and the range of users isn't limited only to students and academic researcher, but reaches out to general public achieving to attract common citizens outside the academia. This doesn't only show the need for public non-commercial space in the city centre, but also expresses people's enthusiasm to make libraries their own shared space.

Finland and Helsinki City Library are not alone in planning a new landmark library in primary locations. There seems to be somewhat of a global trend of building impressive libraries as, just to mention a few, there has been newly opened libraries in Aarhus Denmark, Newcastle England, Ghent Belgium and Halifax Canada and currently under construction or being planned in like in Oslo Norway.

3 Planning the project: Towards participatory practises

In 2007 the Mayor of Helsinki Jussi Pajunen launched a central library review process led by a consult outside of library world Mikko Leisti. The final report of the review process, Heart of the Metropolis – the Heart of Helsinki, (Leisti; Marsio, 2008) was used as a background working paper and laid a foundation for goals and visions of the project.

The review process included ordinary library users to this early developing stage, as different kind of users were interviewed and invited to join group discussions. After the review report was published in early 2008 Helsinki City Library started the planning process in earnest. As the review process' final report outlined user consultation as one of the key elements for the next steps forward, participatory practises were included in the whole planning process. The vision was to model the Central Library planning project as a new kind of inclusive city planning process which would not only ask people's opinion through surveys but actually include them into the planning, thus creating a library which will be truly owned by the citizens.

But how to engage and involve citizens in traditionally rather bureaucratic and distant planning processes? The Central Library project brought about various approaches to this problem and continues to experiment ways in which library users and regular citizens can be brought into different stages of planning processes.

One of the early stages of participatory practises was the launch of the Tree of Dreams in 2010 (Central Library Project, s.a.). It was a digital platform, as well as a real tree touring around the city in different events, collecting citizens' dreams as leaves to its' branches. People were simply asked to write down their dreams and wishes of what the future library might be and what it could offer to the citizens. The Tree of Dreams collected approximately 2 300 ideas. All this material was later categorised, analysed, and further developed into pilot projects and trials developing content and services for the future library.

When thinking of user participation, one aspect of planning has for long been out of reach for normal library users: budgeting. Participatory budgeting was one of the models used in engaging citizens in planning processes and giving library users a say in what kind of services will be offered in public libraries. In 2013, through budgeting workshops, citizens were given a choice how to spend 100 000 euros to develop library services.

From the ideas collected through the Tree of Dreams project eight dreams were chosen to a short list and developed into a pilot proposals. In the autumn of 2013 there were three participatory budgeting workshops (Central Library Project, 2012) where the residents of Helsinki from different backgrounds got together and discussed the pilot proposals and how to spend the assigned sum. The project proposals were individually budgeted beforehand so the threshold to participate was kept low and the workshop participants weren't required special skills for project planning. As a result, four projects from the short list were chosen to be realized in 2014 (Miettinen, s.a.). In addition to the chosen pilot projects the workshops also further developed other plans on the short list which weren't chosen that time around, and created brand new suggestions how to develop future library services.

Through the participatory budgeting project Helsinki City Library acquired concrete directions from the citizens for what kind of public library services are anticipated and needed in the future Central Library. Also, by giving city residents, i.e. the owners of the libraries, a say in financial decision making, Helsinki City Library fulfilled one of public libraries' basic tasks as advancers of democracy. One of the workshop participants stated that it was actually great to see close-range democracy in action (Ibíd.).

Another good example of participatory practise, which has consolidated its status as an ongoing user-thriven development tool, is the Friends of the Central Library. Friends of the Central Library was a pilot project in 2014-2015 and it aimed to engage a diverse group of citizens to the planning process through workshops, questionnaires, and online tasks. The aim was to create a user-developer community by putting together a group that would be a good representative sample consisting of people from different parts of the city, different age groups, sexes, and different set of skills. The emphasis was put on getting on board people who were enthusiastic to influence in decision making and willing to commit to work in the group.

The group members were selected through a method imitating job seeking. The applicants wrote a “job application” describing themselves and giving reasons why they were the perfect candidate to be a Friend of the Central Library. From 95 applicants, 28 were chosen to participate in the pilot phase (Miettinen, 2015, p. 7, p. 17).

From library's point of view piloting a user-developer panel had two main aims. Firstly, again, through engaging regular citizens in depth into the planning process, the City Library got valuable first-hand information from the residents what kind of services was needed and wished for. Also, by involving the users in planning, library professionals get kind of an outsider view to how public library services are perceived, opening new perspectives and opportunities for development. Secondly, through piloting this kind of user participation for the Central Library project Helsinki City Library was able to establish a new permanent tool for development. From the experiences gained during the pilot project, the Friends of the Central Library took a step forward, and the Friends of the Library (Central Library Project, s.a.) was established in 2016 as permanent user-thriven development community for the whole library network of Helsinki. Also, participatory projects create opportunities to democratic participation for citizens and also creates a common feeling of ownership of shared public services.

Throughout the project the nature of participatory measures have changed also according to the needs of the project. Currently (December 2016) the project is in a phase of service design for the Central Library. Through analysing users' needs, certain aspects of services and needs has risen and taken to further development. One of the service design projects is family services and library's functions from families' point of view. The family library planning (Valleala, 2016b) was carried out through workshops with families and service design professionals (Valleala, 2016a). These workshops concentrated to service design as entity rather, than just single services. They outlined directions for usability for the whole building starting from signage and other functionalities, such as parking baby strollers and how to add playfulness to the building. Families are one of the main focuses for the building and the Department of Early Education and Care will be one of the permanent partner located in the building.

Participatory planning has always several dimensions adding value to library planning processes, offering a channel for close-range democracy, but also opening city decision making process to the citizens. One future idea to open up Helsinki City's acquisition processes, while offering the public a chance to influence on interior design decisions of the Central library, is furniture testing. The idea is that residents will get a possibility to test out different pieces of furniture, chairs, tables, etc., and get to vote for their favourites. This could be realised in a way that it also opens up the chain of decisions and measures of city's acquisitions increasing transparency of public spending and decision making.

Participation in planning isn't limited only to users' involvement. In the new Central Library building there will be different partners working under the same roof. As already mentioned, the Department of Early Education and Care will work as a partner in the building as will for example the National Audiovisual Institute and Aalto University. These partners are a vital part of the planning process for a new multifunctional building. The entrance lobby area of the library (Valleala, 2016c) will be a hub for partnership in the library and the lobby's service design is been developed in close cooperation with the different partners.

4 Inclusive architecture competition

Architecture competition is often a phase in public service planning where the actual end-users of the building will be largely kept out. As Helsinki City had lined in its Strategy Programme 2013-2016 involvement and participation as one of the city's core values (City of Helsinki, 2013, p. 3), the Central Library project sought ways to citizens' participation also in this field of planning.

An open international architecture competition for the new Central Library was held in 2012-2013. From early on the competition was kept transparent and people were offered possibilities to view the competition proposals and to give feedback and vote for their favourites. In the first phase of the competition all 540 proposals were gathered into an open exhibition where everyone could browse through the proposed architectural plans. At this exhibition, the visitors were able to comment on the proposed building plans and vote one's favourite by tagging it with a heart. The exhibition attracted 2600 visitors and 2400 votes on a favourite building plan (Central Library Project, 2012). The exhibition was originally scheduled to be open only for a week, but due to a public demand, it got continued for another week.

In the second phase of the competition six proposals were short listed by the jury. During this second phase the proposals were exhibited in the Helsinki City Museum, online, and on touchscreens throughout the city centre. Again at this stage, the public was able to comment the proposals and vote for their favourite building. On the second phase of the competition over 3200 citizens voted for their favourite (Central Library Project, 2016).

Public vote on the future building wasn't the decisive factor for the new building, as the competition winner was chosen by a jury. Nonetheless, having a transparent architecture competition, during which people were invited to view the competition proposals and light-heatedly vote on their favourites, creates a feeling of openness and participation quite different from the usual planning process of a new public building. As stated above, after the winner of the architecture competition was announced in spring 2013, there has been barely any harsh criticism on the building itself. There is no studies done on this issue, but the transparency and inclusiveness of the architectural competition phase might have had an influence on the favourable public opinion. In the public voting during the second phase (Central Library Project, 2013) of the architecture completion, the overall winner, Käännös, came second with 20 % share of the votes.

5 Goals of the Central Library?

As emphasised before, public libraries have a duty to promote democracy and civic participation, and this is also taken as a leading principle in Helsinki City decision making. The future Central Library has many aims and demands to live up to as its function exceeds that of a normal branch library.

At the local level, there is a huge demand for non-commercial public space in the city centre that libraries can offer. A good indicator for this need is the beforementioned experiences of the University of Helsinki main library Kaisa House, where the visitor number has surpassed the original estimates by nearly doubling. Since 2005 a Helsinki City Library's branch library, Library 10, has operated in the Main Post Office Building nearby the future Central Library. Library 10 has been essential to the Central Library project as it has been a working test ground for some of the new services and models for the Central Library now for over a decade. Experiences from Library 10 have also reinforced the claim for more public space in the city centre area as, in spite of its relatively small floor space, only 800 m², the library attracts approximately 2000 visitors per day.

It is estimated that the Central Library will have well over 10 000 daily visits and visitor numbers may reach up to 12 000-13 000 visits a day. This creates huge challenges for the new building, but we believe that with thorough and flexible planning, learning from other libraries' experiences, and taking into account the users' needs these challenges can be answered successfully.

Helsinki City Library's new Central Library will not only be a landmark building in the city centre for the residents of Helsinki. Helsinki City Library functions also as a central library of all public libraries in Finland, which broadens its tasks and responsibilities to cover the needs of the whole country's library field. Also, since being elevated to being a headline project of Finland's 100th year of independence celebrations the new Central Library project has a strong national dimension.

The library will work as a front page of Finnish public libraries since its positive public image can be use in PR work for the whole library network. One of the more concrete functions of the Central Library as a national project is to be a testing ground of new services and partnerships for the whole Finnish library field. Like over the course of the planning process, new services and different kinds of models will be piloted and benchmarked in the building and the results can be enjoyed and further developed all over the country. So the scope of the operations of this library will be not just the City of Helsinki, but the whole country.

6 What does the building reflect?

As shown, the Central Library project has introduced new methods of participatory planning into public planning making the process more democratic and creating a sense of common ownership of the library institution. Also, the building and its services reflect new library thinking where the users are active doers, rather than passive consumers.

There is little sense to build a book depository in one of the best locations of the city centre. The new library will offer traditional library services, like lending books, but the shift also in public's need is more and more from borrowing to doing. The proposal for the new library law (Finnish Government, 2016) in Finland underlines public libraries' duty to promote active citizenship and democracy, but also requires libraries to offer spaces and facilities for learning, working and different leisure activities. This project as a whole has reflected well the spirit of the new law by promoting active citizenship during the planning process, and by continuing doing that after the opening in 2018.

The Central Library will be located in a very central and symbolic site. As a beacon of close range democracy and open culture the new library building will reside between two important cultural institutes, the Musiikkitalo music centre and the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, and opposite the Parliament House, the home of democratic decision making. This location reflects the value given to public libraries in the country as core facilitator of civic democracy and guarantor of access to knowledge and culture for all.

We are trying to build a library that would be a people's library in as broad sense as possible. So how does the Central Library reflect its future users' needs and hopes? The Finns love their libraries, but what are they expecting from their future library? Over the course of this project we have observed that people are looking for free and safe, culturally rich and innovative, public space with possibilities to do and to network with other people, and of course books and other materials to borrow. And coffee.

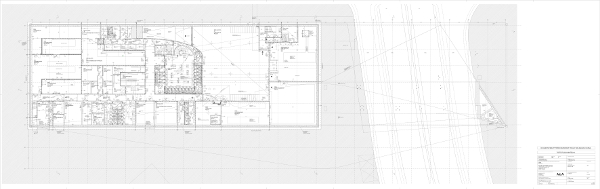

Figure 1. Planning services for the library

Figure 2. On the southern end of the top floor,

a view towards the inside of the library and outwards will be gorgeous

Figure 3. The 'Dream' ('Unelmoi') campaign was a great success

Figure 4. One of the plans for the new Central Library in Helsinki

Bibliography

Central Library Project (2012). Keskustakirjastoehdotukset keräsivät yli 2000 tykkäämistä. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/

2012/06/15/keskustakirjastoehdotukset-kerasivat-yli-2-000-tykkaamista/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Central Library Project (2012). Residents of Helsinki! Help us make budget decisions. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/

en/2012/10/15/residents-of-helsinki-help-us-make-budget-decisions/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Central Library Project (2013). Yli 3000 kaupunkilaista äänesti – suosikki oli the Diagonal Agora.

<http://keskustakirjasto.fi/2013/04/12/yli-3000-kaupunkilaista-aanesti-suosikki-oli-the-diagonal-agora/>.

[Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Central Library Project (2015). Frequently Asked Questions. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/en/frequently-asked-questions/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Central Library Project (2016). Yhdessä. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/yhdessa/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Central Library Project (s.a.). Voice of the City Residents – Participatory Planning. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/

en/voice-of-the-city-residents-participatory-planning/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Central Library Project (s.a.). Keskustakirjaston kaverit. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/yhdessa/kaverit/>.

[Accessed: 12/12/2016].

City of Helsinki (2013). Strategy Programme 2013-2016 <http://www.hel.fi/static/taske/julkaisut/2013/

Strategy_Programme_2013-2016.pdf>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Finnish Government (2016). Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laeiksi yleisistä kirjastoista ja opetus- ja kulttuuritoimen rahoituksesta annetun lain 2 §:n muuttamisesta. <http://valtioneuvosto.fi/paatokset/paatos?decisionId=0900908f804f5e9c>.[Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Helsinki University Library (2016). Finland’s Most Popular Learning Environment Kaisa House Attracts Over 9,000 Visitors per Day. <https://www.helsinki.fi/en/news/finlands-most-popular-learning-environment-kaisa-house-attracts-over-9000-visitors-per-day>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Leisti, Mikko; Marsio, Leena (2008). Heart of the Metropolis – the Heart of Helsinki. <https://www.competitionline.com/upload/downloads/109xx/10948_93071_Centrallibrary_reviewreport.pdf >.

[Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Libraries.fi (2016). Finnish Public Library Statistics. <http://tilastot.kirjastot.fi/?lang=en>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Miettinen, Virve (2015). Prosessi ja toimintamalli KESKUSTAKIRJASTON KAVERIT –kehittäjäyhteisö. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/wp-content/blogs.dir/4/files/2015/03/1-Kuvaus-Keskustakirjaston-kaverit-prosessi-ja-toimintatapa.pdf>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Miettinen, Virve (s.a.). Osallistuva budjetointi, Kaupunkilaiset päättivät rahasta – kirjasto käynnistää valitut pilotit vuonna 2014. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/yhdessa/osallistuvabudjetointi/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Ministry of Education and Culture (2012). Finns are avid readers and library users. <http://okm.fi/OPM/Verkkouutiset/2012/04/kirjastotilastot.html?lang=en>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Ministry of Education and Culture (2013). Arhinmäki: Helsingin keskustakirjastosta Suomen itsenäisyyden 100-vuotisjuhlahanke <http://www.minedu.fi/OPM/Tiedotteet/2013/06/keskuskirjasto.html?lang=fi>.

[Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Sokka, Sakarias; Kangas, Anita; Itkonen, Hannu; Matilainen, Pertti; Räisänen, Petteri (2014). Hyvinvointia myös kulttuuri- ja liikuntapalveluista. Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiö, Sastamala. <http://kaks.fi/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Hyvinvointia-myös-kulttuuri-ja-liikuntapalveluista.pdf>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Valleala, Siru (2016a). How is Central Library Coming About. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/en/2016/09/26/how-is-the-central-library-coming-about/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Valleala, Siru (2016b). Perhekirjasto muotoutuu hyvissä käsissä. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/2016/10/31/perhekirjasto-muotoutuu-hyvissa-kasissa/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

Valleala, Siru (2016c). Aula on käyntikortti kirjastoon. <http://keskustakirjasto.fi/2016/12/08/aula-on-kayntikortti-kirjastoon/>. [Accessed: 12/12/2016].

similar articles in BiD

- Marc, Maria and David : applying user experience design to public libraries. Ferran Ferrer, Núria; Fernández-Ardèvol, Mireia; Nieto, Javier; Fenoll Clarabuch, Carme. (2018)

- El procés d'integració de la primera biblioteca interuniversitària d'Espanya : la Biblioteca del campus universitari de Manresa. Riu Amblàs, Trini. (2015)

- La Biblioteca de la Memòria : 10 anys, 100 testimonis. Una experiencia de la Biblioteca Central d'Igualada. Miret i Solé, M. Teresa. (2012)

- Las bibliotecas públicas de Medellín como motor de cambio social y urbano de la ciudad. Peña Gallego, Luz Estela. (2011)

- Biblioteche pubbliche, città e 'lunga coda' : gli esempi della Biblioteca Sala Borsa di Bologna e degli Idea Stores londinesi. Galluzzi, Anna. (2010)

similar articles in Temària

- Captación de recursos externos en bibliotecas : la práctica del fundraising. Pérez Pulido, Margarita; Gómez Pérez, Teresa. (2013)

- La nueva Biblioteca de Navarra. Elizari Huarte, Juan Francisco. (2011)

- Ejecución del I Plan de Servicios Bibliotecarios de Andalucía: perspectivas de presente y de futuro. Pérez Serradilla, Pastora; Álvarez García, Francisco Javier; Muñoz Míguez, Yolanda; Real Duro, Ana María. (2010)

- De la planeación normativa a la planeación estratégica : el CONPAB y el Plan de desarrollo bibliotecario. Sánchez Vanderkast, Egbert John. (2010)

- La planificación bibliotecaria : un análisis de la literatura científica en el ámbito español entre 1995 i 2007. Bonachera Cano, Francisco José. (2010)

[ more information ]

Creative Commons licence (

Creative Commons licence (