Michael Rene Kristiansson

Associate professor

The Royal School of Library and Information Science

University of Copenhagen

Henrik Jochumsen

Associate professor

The Royal School of Library and Information Science

University of Copenhagen

Abstract

The present article intends to illustrate how entrepreneurship-centered teaching and learning can be implemented in a LIS-specific context while at the same time thematizing the challenges of implementing entrepreneurship in a general university context. The paper presents a concept of teaching and learning that is designed partly to meet academic requirements and partly to work satisfactorily, and in an appropriate manner, in a specifically LIS-related (i.e., a non-business) context. The theoretical basis of this teaching- and learning-related concept is explained and discussed. In addition, the article presents particular experiences, results and achievements obtained in seminars and course units at the Royal School of Library and Information Science, where the concept was developed.

Resum

La finalitat d’aquest article és demostrar de quina manera l’ensenyament i l’aprenentatge centrat en l’emprenedoria es pot implementar en el context específic de la Biblioteconomia i la Documentació (BID) i alhora exposar els reptes que representa implementar l’emprenedoria en el context universitari general. Es presenta un concepte d’ensenyament i aprenentatge que s’ha dissenyat per satisfer els requisits acadèmics i també per treballar de manera satisfactòria i rellevant en el context de la Biblioteconomia i la Documentació (és a dir, en un context no empresarial). S’expliquen i analitzen les bases teòriques d’aquest concepte d’ensenyament i aprenentatge i, a més, es presenten les experiències concretes, els resultats i els assoliments dels seminaris i els cursos a la Det Informationsvidenskabelige Akademi on s’ha desenvolupat aquest concepte.

Resumen

La finalidad de este artículo es demostrar de qué manera la enseñanza y el aprendizaje centrado en el emprendimiento puede implementarse en el contexto específico de la Biblioteconomía y la Documentación (ByD) y al mismo tiempo exponer los retos que representa implementar el emprendimiento en el contexto universitario general. Se presenta un concepto de enseñanza y aprendizaje que se ha diseñado para satisfacer los requisitos académicos y también para trabajar de manera satisfactoria y relevante en el contexto de la Biblioteconomía y la Documentación (es decir, en un contexto no empresarial). Se explican y analizan las bases teóricas de este concepto de enseñanza y aprendizaje y, además, se presentan las experiencias concretas, los resultados y los logros de los seminarios y los cursos en la Det Informationsvidenskabelige Akademi donde se ha desarrollado este concepto.

1 Introduction

Europe needs to stimulate the entrepreneurial mindsets of young people […] The important role of education in promoting more entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviours is now widely recognized. However, the benefits of entrepreneurship education are not limited to start-ups, innovative ventures and new jobs. Entrepreneurship refers to an individual’s ability to turn ideas into action and is therefore a key competence for all, helping young people to be more creative and self-confident in whatever they undertake. (European Commission, 2008, p. 7).

Entrepreneurship is an increasingly central phenomenon in contemporary society. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) proposes to foster an entrepreneurial spirit in general (OECD, 2010; OECD, 2015, p. 54–60) and the European Commission suggests focusing school curricula on creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship (European Commission, 2010). Fully appreciating the importance of this and despite the challenges involved, the institutions have entered what was once the domain of business schools and implemented entrepreneurship education in the curricula of many universities around the world (West; Gatewood; Shaver, 2009a). Efforts are even being made to establish entrepreneurial universities (NCEE, 2013; Fayolle; Redford, 2014). In short, designing and implementing courses in entrepreneurship can answer a major societal and international need to train enterprising and dynamic individuals to use and develop the professional knowledge they gain from university in a practical context, for their own benefit and for the advancement of their profession and society. The greater the demands that technological progress makes on individuals to recreate their professional profile, the more relevant entrepreneurship becomes for both the labor market in general and the LIS community and LIS education in particular.

2 Problem statements

First, there is no consensus on the concept of ‘entrepreneurship’, which can take on many meanings and is closely related to other notions such as ‘creativity’, ‘value creation’ and ‘innovation’. The use of these terms varies from one professional environment to another. By referring to researchers such as Brazeal and Herbert (1999) and Low (2001), French professors in entrepreneurship and innovation management and strategy cited in Fayolle and Gailly (2008) state that, at ontological and theoretical levels, there is no consensus on what entrepreneurship is.

Second, this lack of consensus extends to the debate about how to manage entrepreneurship education or organize entrepreneurship teaching (Gibb, 2007). In the words of Fayolle citing Brazeal and Herbert (1999) and Low (2001), “the field is very young, emergent and in adolescence (or infancy) phase” (Fayolle, 2007).

Third, the task of designing and implementing courses in entrepreneurship involves a number of challenges, including educational and didactic considerations. One question often encountered in the literature is whether entrepreneurship can be taught at all (Henry, Hill; Leitch, 2005a, 2005b). If we assume that entrepreneurship can be learned, which form of education/teaching should be used? What are the goals of entrepreneurship education? And which are the pedagogic tools?

2.1 Problem

The present paper addresses the challenge of implementing entrepreneurship, which is a practice-related discipline, in higher education environments whose core activities are teaching and research. We thematize this problem by identifying and illustrating a concept of teaching and learning, called effectuation, which we have tailored to suit LIS studies at the Royal School of Library and Information Science in Denmark (hereafter, RSLIS). We will clarify and qualify the problem of implementing entrepreneurship teaching in these studies by reporting on our experience of experimenting with effectuation at the RSLIS.

Considering it to be a promising method (Fayolle; Gailly, 2008, p. 584), the RSLIS has experimented with effectuation in teaching settings for a number of years. Recently, we have employed the method in our course offering Entrepreneurship and partnership. This article describes how we did this in the following manner: first, we will present effectuation as a general method for entrepreneurship teaching; next, we will present and discuss how our institution developed the effectuation-based course Entrepreneurship and partnership; third, we will present and discuss our use of effectuation from the point of view of the participating students and external examiners; and finally, we will consider the scope for and relevance of continuing this work and taking this concept of teaching further.

3 The theoretical framework: the effectuation model and its principles

Our institution chose effectuation as its point of departure because the method is generally applicable to different fields and need not be directly linked to a business mindset. As explained below, these fields include entrepreneurship education in the humanities and, in our case, in LIS studies.

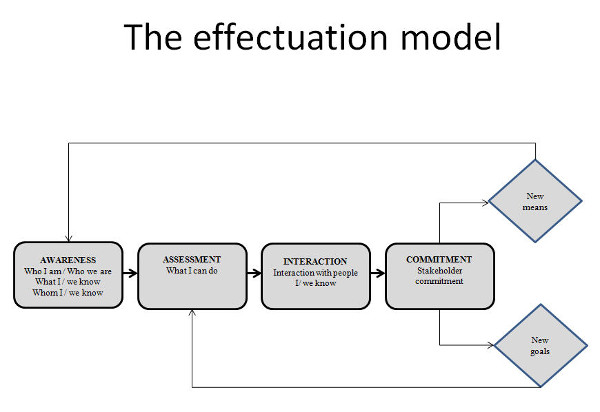

The term ‘effectuation’ is best understood in the context of its opposite, ‘causation’ (for example, see Nielsen, 2012). Both terms have been formulated by the Indian-American professor of business administration Saras Sarasvathy (2001, 2008). Causation describes the traditional way entrepreneurship is created, meaning through planning. Causation is based on project objectives, meaning that it uses causal logic to establish project aims, which are in turn typically based on predictions about the future. Thus, the aim of causation is to pursue an opportunity that typically appears during the analysis of the external environment. In contrast, effectuation is based on the means that the entrepreneur — in our case, the students or novice entrepreneurs — either have or can activate with relative ease. This is the first step in the effectuation model. By creating projects based on the students’ own existing means, Sarasvathy argues, we can ensure that entrepreneurship does not remain the privilege of a minority (Read et al., 2011).

The second step in the effectuation model is when the entrepreneur / student entrepreneur assesses the possibility of creating a project. The third step in the model is when the student entrepreneur interacts with other people, including fellow students: in other words, this is the moment when students contact local social networks and raise interest in a specific project or in the possibility of reaching a common agreement about what a project might entail. The point is that fellow students can be said to constitute a close network for the individual student. In the classroom, the students introduce themselves to their fellow students through formal presentations made to the group as a whole, explaining who they are, what they know and who they know. The underlying idea can be expressed as follows: based on this presentation, the students will gather together to conduct a joint project.

Thus, the first part of the effectuation model operates as a learning tool insofar as students become aware of their own and others’ personal resources. The second part serves as an assessment tool in the sense that students decide what kind of project they are able to implement by their own means. The third and fourth parts are about interacting with potential stakeholders and making stakeholders partners.

Figure 1: The effectuation model

4 Implementing effectuation at the RSLIS

4.1 The teaching concept

The RSLIS course Entrepreneurship and partnership uses the framework of an educational concept developed especially for entrepreneurship education. Carefully developed on the basis of studies of the literature on entrepreneurship education, the teaching concept has been put to the test and adjusted in the light of the experiences derived from a run of 15 experimental courses conducted in the period 2010–2015. The concept has been systematically developed on the basis of ongoing evaluation and the review of previous courses, making it the result of an experimental, iterative and heuristic process. The following section describes the main processes involved in two recent editions of the course.

4.2 The course

The edition of Entrepreneurship and partnership presented in this paper was offered in the spring of 2014 and repeated in the spring of 2015. The course was offered at a bachelor’s degree level and in each edition there was an average of 25 students, meaning that about 50 students completed the course. The course was funded by the Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship – Young Enterprise.

Normally, when students are assigned a project, they are free to choose both the problem and the methodological approach within the subject of the unit/module. But the special feature of this project assignment was that students were required to address a pre-defined problem statement and adhere to a pre-agreed method. From the outset, all the students studied the same problem and applied the same method, namely effectuation. In other words, they had to apply effectuation as a method to initiate and legitimize an entrepreneurial project.

The premise was that the students would become deeply involved in the effectuation theory and methodology, that they would eventually understand it and that they would be able to apply it in practice. The course program included both theory and practice. As mentioned above, the practical component consisted of two main activities: the initiation of the project and the project’s legitimization. In this component, the students took the initiative to design an entrepreneurial project on their own and, at the same time, they legitimized that project by having fellow students and people from outside the university (friends, family, acquaintances) engage in the project in one way or another. Thus, the students gained practical experience with the initial stages of an entrepreneurship project. To complete the theoretical component of the course, they needed to explain and reflect on their use of effectuation as a theory and method. The practical and theoretical components were given equal importance.

4.3 The challenge of implementing entrepreneurship in academia: a debate

It is a great challenge for a university to harmonize a practice-oriented approach to entrepreneurship with an academic-theoretical tradition. The balance is not that easy to achieve. Entrepreneurship requires action competence, meaning the ability to take the initiative, to act and be constructive. On the other hand, the academic tradition is first and foremost about being critical and the challenge is to have the students commit themselves to the practical work and make an entrepreneurial project real. All in all, the balance between the two is not easy to achieve.

One of the problems is that university curricula often do not allow assessors to evaluate the students according to practical parameters such as action competence and reward those students who actually succeed with entrepreneurship. The challenge may be structural insofar as entrepreneurship takes time, which the university scheduling of modules of shorter duration or the classic semester division may be ill-suited for. Courses are completed within one semester and do not extend over several semesters. But the problem can also be due to the university’s reluctance to accept and honor practical skills in the way it values theoretical skills.

By weighting academic-theoretical requirements for students, the RSLIS curriculum relating to the bachelor’s degree in the fourth semester is no exception. With a pre-given curriculum it is our challenge as educators to interpret the curriculum’s academic-theoretical requirements so that these can match the requirements of entrepreneurship. The course Entrepreneurship and partnership tries to meet this challenge – the conflict of theory versus practice – by setting high standards for both practice and theory.

The curriculum of the bachelor’s degree in the fourth semester states that through project work the students should acquire the ability to analyze and discuss relevant theoretical and methodological issues. In addition, they should acquire the ability to reflect on theory of science-specific positions within the subject area of the theme-specific unit. The objectives of the curriculum are then divided into knowledge, skills, and competences. In terms of knowledge acquisition, students should possess knowledge about theories and methods, which they should be able to understand and discuss, and they should be able to understand theory of science-relevant positions of significance to the theories and methods applied.

Regarding skills, the students should be able to formulate a relevant problem, apply theories and methods to it and analyze the problem in a consistent and coherent manner.

And finally, regarding competences, the students should be able to demonstrate in-depth study performance using a critical, theoretical and analytically discursive and reflective approach, and also reflect on the methodological and theory of science-related aspects of the problem chosen.

In the two editions of the course examined here, our interpretation of the curriculum meant that the students would embark upon an entrepreneurship project using the effectuation model and we placed special emphasis on having students attempt to build partnerships. Accordingly, we set the curriculum and syllabus objectives as follows:

- the students should gain knowledge about entrepreneurship theory and methods, especially effectuation and causation;

- students should conceive and complete an entrepreneurship project based on the effectuation model;

- students are required to present the project to stakeholders in order to gain their commitment and secure partnerships;

- the project should be approached from a theory of science perspective.

The students also needed to explain the project process in both practical and theoretical terms and describe/analyze the interaction between theory and practice.

In short, the students in the two editions of the course needed to do three things: initiate an entrepreneurship project in accordance with the effectuation model; evaluate the development of the process; and describe the relationship between theory and practice in the process sequence.

The course was assessed through an external examination in the form of a written paper, which was defended orally. This requirement was therefore similar to those involved in a traditional student paper in an academic setting. In total, there were six parts to the written paper : a summary or abstract; a description of the issue to be examined (problem formulation); a discussion of the method(s) applied; an analysis; a presentation of the findings and a conclusion; and a list of sources.

Note that students were not required to carry out a project in practice and that they only needed to secure documentation from stakeholders outside the university indicating their commitment. But while the process may therefore appear to have been merely an exercise in academic writing — in providing evidence of an ability to prepare an accurate and rigorous written presentation of an entrepreneurship project — in order to actually do this the students needed to generate and present empirical data in the form of an entrepreneurial project they had initiated and legitimized themselves.

To sum up, the aim of the course was twofold: first, through a self-paced initiative, students were expected to put an effectuation process into practice; and second, they were required to reflect on the process from a theory of science perspective. And as previously mentioned, the required end product was a project assignment with a traditional academic structure.

5 Experiences

In this section we will describe and discuss the experience of the course from the point of view of the external examiners.

First of all, it was relatively easy to assess whether the students had gained knowledge about entrepreneurship theory and methods (in this case, effectuation and causation). It was also easy to assess whether they could apply entrepreneurship theory and methods at a conceptual and theoretical level, classify their project in a theoretical framework and understand the interaction between theory and practice.

A very important part of the effectuation method (and thus also an important part of the exam) was the requirement for students to secure documented commitment from a partner. Within the project framework, this requirement was typically expressed through a reference to the correspondence between the students and a partner (e.g., emails or a logbook) which included a commitment, a prior agreement or some other response from the partner.

But it was somewhat more difficult to measure the students’ competence to take action in relation to entrepreneurship or to determine their employability, particularly in the written part of the exam or study paper. The oral exam provided a better forum for estimating students’ competence to act and assessing their employability.

Most students tried to put an entrepreneurship project into practice, even though a small number remained academic and hypothetical. But as the authors of this article, our experience suggests that it is also relatively easy to assess students’ abilities if the scale of assessment covers the principles and steps in the effectuation model, meaning the extent to which the students have gained real experience and are also able to reflect on the process, on what they have gained and their degree of control over the four processes awareness, assessment, interaction, and creating agreements (i.e., commitment and forming a partnership).

The logbook where the students recorded their actions and thoughts on a daily basis throughout the course period was clearly very suitable for assessing their degree of awareness and discernment, as well as their ability to interact with others. In short, the logbook provided the external examiners with the student’s own measured reflections on the subject of the entrepreneurial process he or she had gone through. The logbook procedure also helped determine students’ capacity to commit themselves to their entrepreneurship projects, meaning their employability.

6 Conclusions

This article presents and discusses a university course on entrepreneurship entitled Entrepreneurship and partnership, the theoretical bases of this course and the experience we gained from implementing it.

Our challenge was to identify a methodological approach which could be applied to a university context, specifically to studies in LIS. Our experience suggests that in the concept of effectuation we identified a theory within entrepreneurship-oriented teaching and learning activities that could be advantageously applied to LIS as an academic discipline. However, it also proved necessary to modify the original form of the effectuation method to tailor it to the university’s academic demands in general and to in its studies in the humanities in particular, specifically to LIS.

We are convinced that important progress was made. At the same time we are also sure there is considerable scope for further exploration and development within this promising field; and that in the years to come, we may help our students’ competences provide a closer match with the demands of the labor market, ensuring that they are better prepared to contribute to entrepreneurial processes in economic, social and cultural projects of every kind.

7 References

Brazeal, D. V.; Herbert, T. T. (1999). ″The genesis of entrepreneurship″. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, vol. 23, no. 3, p. 29–45.

European Commission (2008). Best procedure project. Entrepreneurship in higher education, especially within non-business studies. Final report of the expert group. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2010). Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Communication from the Commission. Brussels: European Commission. [COM(2010) 2020].

Fayolle A.; Gailly, B. (2008). ″From craft to science″. Journal of European Industrial Training, vol. 32, no. 7, p. 569–593.

Fayolle A. (ed.) (2007). Handbook of research in entrepreneurship education: A general perspective, vol. 1. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fayolle, A.; Redford, D. T. (2014). Handbook on the Entrepreneurial University. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gibb, A. (2007). ″Creating the entrepreneurial university. Do we need a wholly different model of entrepreneurship?″ In: Fayolle A. (ed.).Handbook of research in entrepreneurship education. A general perspective, vol. 1, p. 67–97. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Henry, C.; Hill, F.; Leitch, C. (2005a). ″Entrepreneurship education and training: Can entrepreneurship be taught? Part 1″. Education and Training, vol. 47, no. 2, p. 98–111.

Henry, C.; Hill, F.; Leitch, C. (2005b). ″Entrepreneurship Education and Training. Can entrepreneurship be taught? Part 2″. Education and Training, vol. 47, no. 3, p. 158–169.

Low, M. B. (2001).″The adolescence of entrepreneurship research: specification of purpose″. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, vol. 25, no. 4, p. 17–26.

Nielsen, S. L.; Klyver, K.; Evald, M.; Bager, T. (2012). Entrepreneurship in Theory and Practice: Paradoxes in play. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

OECD (2010). The OECD Innovation Strategy. Getting a Head Start on Tomorrow. Paris: OECD.

OECD (2015). The Innovation Imperative. Contributing to Productivity, Growth and Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Read, S.; Sarasvathy, S.; Dew, N.; Wiltbank, R.; Ohlsson, A.-V. (2011). Effectual Entrepreneurship. London: Routledge.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). ″Causation and effectuation. Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency″. The Academy of Management Review, vol. 26, no. 2, p. 243–63.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Effectuation. Elements of entrepreneurial expertise. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, New Horizons in Entrepreneurship Series.

The National Centre for Entrepreneurship in Education (NCEE) (2013). The entrepreneurial university. From concept to action. Coventry, UK: Coventry University Technology Park.

West, P. G.; Gatewood, E. J.; Shaver, K. G. (2009). Legitimacy across the university. Yet another entrepreneurial challenge. In: West, P. G.; Gatewood, E. J.; Shaver, K. G. (eds.). Handbook of university-wide entrepreneurship education. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 1–11.

Creative Commons licence (

Creative Commons licence (