1 Introduction

“Between the birth of the world and 2003, there were five exabytes of information created. We [now] create five exabytes every two days” (King, 2013).

One important consequence of access to this massive increase in information production is that it creates more opportunity for informal personal learning than ever before. As the growing volume of information on the internet feeds independent personal learning then increased demand for more learning facilitation and support is generated. Rather than being a headache for the library, in terms of collections and holding, it is an opportunity —an opportunity for libraries, particularly academic libraries— to claim their place at the heart of learning activity and perhaps to shape the future of independent personal learning.

So what should library space be like in a world where the process(es) of learning are a key consideration in their design and why? Thinking about future space is a risky business —as Stewart Brand (Brand, 1995) points out every new [or refurbished] library is a “prediction about the future”. Although new spaces have to be fit for purpose on their first day of opening, they must also be fit for the unknown future. Being fit for the future is the biggest challenge facing any library, because as Brand also writes “predictions [about the future] are always wrong!”.

The aim of this paper is to examine what is happening with society, learning, technology, and experiences that can inform the development of university library spaces to ensure that they stimulate and support the all-important learning that takes place outside the classroom making libraries fit for the 21st century.

2 What’s happening with society

Ken Robinson (2013) claims that: “Current systems of education were not designed to meet the challenges we now face. They were developed to meet the needs of a former age. Reform is not enough: they need to be transformed”.

Continuing to educate using an “industrial” approach that Robinson (Robinson, 2013) refers to is highly questionable at the current stage of societal development described by Pink (Pink, 2005) in his book “A Whole New Mind”. Pink sees a societal transition over the past 200 years from agriculture to industry and, eventually, to an age of information/knowledge. Much of what we currently read, what determines how we configure our libraries, and what we “teach” in our libraries relates to this information society and the methodologies we use to teach it are informed by those instructional approaches of the industrial age. Pink, however, sees a new and significant societal shift that goes beyond information/knowledge to a conceptual society —a society that values personal attributes such as creativity and empathy as the most important individual and collective societal assets. This conceptual society is about creative capacity and the ability to generate new thinking and ideas that forms the new basis for global participation by the individual and drives national competitiveness —an ideas economy.

Education is the resource that we have to be competitive in such an ideas economy so rethinking how we can shift our education system to meet this challenge is essential. As part of that education system, the academic library needs to ensure that the design of its space is linked to both the activities of teachers and learners. Freeman (2005) sees libraries “as an extension of the classroom” concluding that “library space needs to embody new pedagogies, including collaborative and interactive modalities”. In most universities, there has been an increasing emphasis on how learners learn through informal means outside the classroom over the past two decades. When lectures are “delivered” on mass online, as in MOOCS, what happens outside of these events becomes the “real” learning. Libraries and their spaces, consequently, have a more important role than ever before as places of learning in what is becoming a truly mass education system. In such a “flipped” system, libraries need a vision and purpose about people and how they learn and a willingness, through the environments they offer, to make a real contribution to the learning that is appropriate to the conceptual society. 21st century libraries are at the confluence of the information and ideas economies valuing and supporting the learner as a producer, rather than simply a consumer, and recognising the reality of the participatory culture described by Jenkins (2013).

3 In short the library’s contribution to learning

Academic libraries have always been places of learning, supporting personal exploration of information and knowledge held in their collections by learners and researchers alike. Instructional materials and courses on how to make best use of the resources held by the library and how to access its services have always been part of the work of the library. This role further developed with the growth of e-resources. In these ways libraries already an important part in learning but there remains much more scope for them play a greater role in community, societal and individual learning by developing support for learners and, in particular, moving the emphasis from support through instruction to facilitating the construction of concepts, knowledge and understanding that deep learning requires. Understanding learning support that goes beyond instruction is an important first step in assuming a greater role in learning for the library.

With this shift comes a second most important change of perspective —consumers in the modern library become producers. As Dempsey (2010) suggests the outside-in library of the past, that collects resources in a place for users to use, needs to become the inside-out library that enables users to become producers within the library making their products available beyond the confines of the building— development of the library “collection” then becomes both acquisition and production. Clearly as we revise our view of learners as consumers of information to one of constructors and producers of knowledge we need to rethink our library and learning space provision and the contribution that the library can make to communal and individual learning.

4 What is happening with learning?

John Seely Brown (Brown; Duguid, 2000) believes that: “learning is a remarkably social process. In truth, it occurs not as a response to teaching, but rather as a result of a social framework that fosters learning”. This theme of the orality and sociality of learning, which sees knowledge as both a social construct and a result of social interaction, is rooted in a Vygotskian social constructivist view of the world (Pass, 2004). Our common understanding of “social” is devoid of a learning perspective and focuses on the importance of interactions with others in informal get-togethers. However, the main activity in such gatherings is conversation and as Seely Brown sees it: “All learning starts with conversation”.

This simple statement is easy to dismiss but in fact describes a far-reaching and deeply important idea extending our view of what “social” is from the sociality of interaction to the sociality of learning. Conversation, an important component of much human interaction, plays a key role in the whole range of learning (and teaching) activities and involves not just conversations with peers and teachers but also with materials, resources and technologies (for a more detailed conversational framework and discussion see Laurillard, 2002). Conversation contributes to a wide spectrum of learning activities that include acquisition and inquiry, discussion, practice, and collaboration and production. Conversation is also a key component of a wide range of current learning theories including social constructivism (peers checking their understanding through conversation), instructionism (teachers’ presentation and explanations), constructionism (conversations with ourselves that modify our conceptual frameworks), and situated learning (co-creating knowledge in the situation you intend to use it in). Conversation, until relatively recently, was not an activity that that had a good fit with the library.

The importance of conversation to effective learning is clear in both social and personal contexts as is the point that the current focus on social learning is not a replacement for all that has gone before but more correctly an attempt to address the universality of one-way conversations that characterize instruction. The opportunity for libraries, as learning places, is to contribute to this rebalancing by enabling conversations of all types. The challenge is, through the facilities we create and the services we offer in our libraries and learning spaces, to rebalance education systems that have for too long focused too heavily on instruction whilst still retaining sufficient balance recognizing that learning is socio-personal and diverse. New library and learning space should reflect the diversity of conversational possibility. Carefully constructed social learning space with a variety that supports all types of conversation from active engagement with others to solitary reflection enables the broadest range of learning —the creation of social space alone does not.

Diversity of conversation is one perspective. Howard Gardner’s research (Gardner, 2006, 1999, 1993) in educational psychology makes it clear that intelligence is not a singular concept but that learners all have a wide range of facets to their personal intelligence —and consequently are all intelligently different providing a second dimension to learning related diversity. The clear message from this is the existence of individual difference and the inherent variety of need exhibited by learners —demanding diversity of spaces. There is also now an acknowledgement that learning has an important emotional component. Positive and negative emotions can improve or hinder learning. Jensen (Jensen, 2005) reminds us that not only are emotions important as drivers and barriers to learning but that they are present all the time, connected to our behaviours and transient —continuously dynamically changing. It is also clear that the dynamic nature of need is complex involving as it does emotions. Personality and intelligence factors. The result is a complexity of the personal context in which people learn that demands that we strive continually to understand in experiential terms what environments might work and what will not. Spaces that we create can improve or hinder learning through the subtle effects that they have on those who inhabit them. Italian teacher and psychologist Loris Malaguzzi believed that children develop through interactions, first with the adults in their lives —parents and teachers— then with their peers, and ultimately with the environment around them. Malaguzzi believed that the environment is the third teacher.

The reality of changing user expectations and 21st century ideas about learning encourages a shift in the spaces that our libraries should provide. Lanke (2013) expresses this clearly in the idea that “Today’s great libraries are transforming from quiet buildings with a loud room or two to loud buildings with a quiet room”.

5 It is the experience of physical space that is important

According to Richard Florida (2003), from his work with focus groups of creative class people, what is important are experiences: “Experiences are replacing goods and services because they stimulate our creative faculties and enhance our creative capacities. This active, experiential lifestyle is spreading and becoming more prevalent in society…”

Writing about the “Experience Economy” Pine and Gilmore (1999) describe a progression of customer needs from commodities to goods then services and ultimately experiences. Providing excellent library experiences should be one of the primary aims of any library and learning space development. How users experience the library is dependent on the quality of the space, how it is organised and the services provided within the space. Where space and services are designed and managed to fit perfectly with expectations, and change over time as expectations change, excellent experiences will be the outcome.

Making library buildings “an experience” is a fresh perspective that demands we think about their look and feel in considerable detail. Florida’s work illustrates that place remains important to members of the conceptual age and the importance of thinking of our buildings as experiences cannot be underestimated. The designer Karim Rashid expresses this well in point 43 (of 50) of his manifesto: “Experience is the most important part of living, and the exchange of ideas and human contact is all there really is” (Nickels, 2013). Space and objects can encourage increased experiences or detract from our experiences”. Such thinking takes us beyond customer service to a requirement for intimate knowledge of those that use our facilities that translates into an understanding of how they experience, and how they feel about how they experience our libraries.

6 Trends and ideas. Open plan space

The most common modern approach is to provide open plan space. Open plan deals with some of the uncertainty mentioned above and brings the promise of ongoing reconfiguration as the building learns, through use and emerging trends, what is required of it as a space. Flexibility for the future is the key desirable feature of these spaces. Most importantly, in the most successful implementations of open plan, there has been careful consideration of how the areas connect avoiding unnecessary traffic through the building. It is harder to be wrong about the future with open space that offers endless possibility. But open plan is not without its critics who focus on the potential for noise and lack of privacy. However, careful selection and positioning of furniture and location of book stacks contains noise and provides some semi-private space (see below) that deals well with this criticism. Importantly open plan also provides the opportunity to regularly “redesign” the space by introducing new structures and items of furniture or rearranging existing furniture (relatively straightforward) and book stacks (more difficult and resource intensive) to create quiet and noisy zones for example.

7 Variety and flexibility

From a learning perspective a variety of spaces that acknowledge individual difference, conversational learning and emotional factors, rather than ignores them, demands a new approach to what we provide in our libraries and how we provide it. One clear message emerges —there is a wide range individual difference amongst our library users that stems from an inherent variety of need and that these needs change over time. This suggests a real requirement for variety of space provision in our libraries to give learners real choice. But this variety is not about separate space silos. It is about recognising that we are social animals with distinctive contributions and that we construct our frameworks of understanding within a powerful conversational framework that includes a continuum of interactions with resources and technology, listening, participating, contributing, reflecting and producing. Learning will always be the responsibility of the individual; libraries currently, through their resource collections, supply the resource inputs; they need to do more to embrace, encourage, stimulate and promote the producers of future knowledge. Shifting the focus of library space to the activities of people as learners and producers in the context of the emerging conceptual age is the key challenge for the library.

8 Semi-private space

Included in the category of “other fit out items” —items that stand within an open plan space and provide a degree of privacy— are what I call semi-private spaces. These can be used for two reasons. Firstly, to shield the users of the library from the less tidy parts of operations such as self-service machines, printers and book trolleys by enclosing them in pods or other similar structures. Secondly to partly separate users of the library from others to allow individual or group work within open plan space that feels as if you are working in a private room.

In the first category structures can be constructed such as printer pods, trolley bays and self-service machine housings that not only serve to “hide” these items but also enhance the environment. For example, pods to house printing and photocopy services contain the noise and untidiness of the machines but also create opportunities for interest, through the use of graphics inside the pod, on an otherwise open floor.

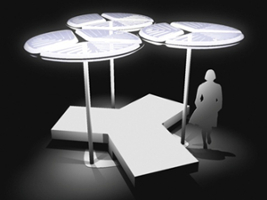

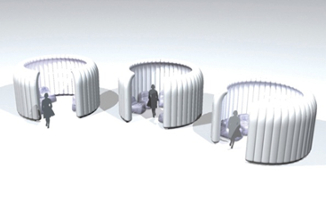

The second point is the separation for members of the library who want to work individually or in a small group. Most new developments achieve this with some form of banquette, or diner style, seating for example. Carefully arranged shelving to form “book walls” also works well. Bespoke semi-private structures that provide varying degrees of enclosure and sound separation such as mobile canopies, inflatable igloos, and umbrellas as illustrated below (figure 1.) are also useful.

Figure 1. Concept for “street umbrellas” and inflatable “igloos” for the Saltire Centre at Glasgow Caledonian University

These “temporary semi-private” structures are recognisably different from other furniture and fittings in the space and, as their continuous use and popularity suggest, appeal to users in other ways than just their ability to reduce noise. They serve to structure the space from a space planning point of view whilst interfering little with its flexibility. This recognition of the ability of structures to act as furniture and furniture to structure a space provides the endless opportunities for flexibility of design in open plan spaces.

9 Flow

The creation of space is not, however, merely about the range and balance of a variety of spaces (although these are important) but is also about how they interrelate and flow from one space to another. It is crucial to ensure that a fragmented feel is avoided and that, in the case of a part refurbishment, the “bolt on” facility is integrated into the whole. Much has been written about the library as Third Place (Oldenburg, 1999), those places that are not work and not home but that hold special significance to those who visit and use them. According to Mikunda (Mikunda, 2006) the creation of a third place should have a “golden thread” (flow) running through it that encourages users to “mall” and to explore it – a development of the idea of the “architectural promenade” identified by Le Courbusier (What is an architectural promenade, 2015). Using tricks of suspense and revelation places also often have a landmark or core attraction that arouses curiosity —the “wow” that is so often found in new spaces and buildings that stimulates the visitor to “mall” or “promenade” and explore the space. Examples include public works of art, impressive atrium spaces and the furniture itself deployed in the space. Flow facilitates user journeys through the space. Landmarks and core attractions provide destinations.

In summary: developing a new library or learning space is an act of creativity. Rather than retreat to a place of comfortable certainty that repeats what we already know, projects need to use the tools mentioned above to experiment and to play their part in the evolution of the library ecosystem providing a platform for future innovation.

Bibliography

Brand, S. (1995). How buildings learn: What happens to them after they are built. New York: Penguin Books.

Dempsey, L. (2010). “Outside-in and Inside-out Redux”, Lorcan Dempsey’s weblog, 6th June 2010. <http://orweblog.oclc.org/outside-in-and-inside-out-redux/>. [Accessed: 28/12/2016].

Florida, R. (2003). The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

Freeman, G. T. (2005). “Changes in learning patterns, technology and use”, In: Library as place: rethinking roles, rethinking space. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources.

Gardner, H. (2006). The development and education of the mind: the selected works of Howard Gardner. London; New York: Routledge.

— (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books.

— (1993). Frames of Mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Jenkins H. (2013). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st Century, an occasional paper from The John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, MIT. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jensen, E. (2005). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Books.

King, B. (2013). Too Much Content: a world of exponential information growth. The Huffington Post Tech, 20th May. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/brett-king/too-much-content-a-world-_b_809677.html>.

[Accessed: 20/05/2013].

Lanke, R. D. (2013). Expect more: Demanding better libraries for today’s complex world (p. 32). [S.l.]: R. David Lankes.

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. New York: Routledge; Falmer.

Mikunda, C. (2006). Brand lands, hot spots & cool spaces: welcome to the third place and the total marketing experience. London: Kogan Page.

Nickels, T. (2013). “Today’s dose of designspiration: Karim Rashid’s ‘Karimanifesto'”, In: Design Log. <https://tianickels.wordpress.com/2013/04/18/todays-dose-of-designspiration-karim-rashids-karimanifesto/>. [Accessed: 28/12/2016].

Oldenburg, R. (1999). The great good place: cafés, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day, New York: Marlowe.

Pass, S. (2004). Parallel paths to constructivism: Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky. Greenwich, CT.: Information Age Publishing.

Pine, J. B.; Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: work is theatre & every business a stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Pink, D. H. (2005). A whole new mind: How to thrive in the new conceptual age. London: Cyan Books.

Robinson, K. (2013). Out of our minds: learning to be creative. Chichester, UK: Capstone Publishing.

Seely Brown, J.; Duguid, P. (2000). The social life of information. Brighton, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Sweney, M. (2011). UK ebook sales rise 20 % to £180m, 3/05/2011. <https://www.theguardian.com/media/2011/may/03/ebook-sales-amazon-kindle>. [Accessed: 12/04/2017].

Watson, L. (ed.) (2013). Better library and learning space: Projects, trends and ideas. London: Facet Publishing.

“What is an architectural promenade?” (2015). Quora.com. <https://www.quora.com/What-is-an-architectural-promenade>. [Accessed: 28/12/2016].

Creative Commons licence (

Creative Commons licence (