[Versió catalana | Versió castellana]

Mireia Alcalá Ponce de León

Bachelor’s degree holder in Information Science

Universitat de Barcelona

Abstract

In recent years, the growth of web-based social participation and the open source movement have prompted a number of initiatives, including the movement known as crowdsourcing . This paper examines crowdsourcing as a volunteering phenomenon and considers what motivates individuals to participate in crowdsourcing. In addition, the paper reviews the main projects in mass transcription being made in memory institutions worldwide (libraries, archives, museums and galleries), briefly introducing each project and analyzing its main features. Finally, a selection of best practices is offered to guide institutions in the implementation of mass transcription projects.

Resum

En els últims anys, la participació social per mitjà de la xarxa ha esdevingut essencial en alguns àmbits. En aquest treball es fa referència a aquest tipus de moviment anomenat “crowdsourcing” o de “proveïment participatiu”, a la figura del voluntariat i a les motivacions que el porten a participar-hi. A més, es mostra un recull dels principals projectes de “crowdsourcing” sobre transcripcions massives realitzats a les institucions de la memòria (biblioteques, arxius, museus i les galeries) a nivell internacional. Mitjançant l’anàlisi d’aquests projectes, se’n revisen les característiques a través d’uns indicadors creats especialment per a aquests tipus d’iniciatives i, a partir d’aquí, es proposen unes bones pràctiques que cal preveure en el disseny de projectes de transcripcions massives.

Resumen

En los últimos años, la participación social a través de la red se ha convertido en esencial en algunos ámbitos. En este trabajo se hace referencia a este tipo de movimientos llamados “crowdsourcing” o de “abastecimiento participativo”, en la figura del voluntariado y en las motivaciones que le llevan a participar. Además, se muestra una recopilación de los principales proyectos de “crowdsourcing” sobre transcripciones masivas realizados en las instituciones de la memoria (bibliotecas, archivos, museos y las galerías) a nivel internacional. Mediante el análisis de estos proyectos, se revisan las características a través de unos indicadores creados especialmente para este tipo de iniciativas y, a partir de ahí, se proponen unas buenas prácticas que se deben de contemplar en el diseño de proyectos de transcripciones masivas.

1 Introduction

The increase in the last years of the digitalizations by the institutions of the memory has been favored by the consolidation and the improvement of the Information and Communication Technologies. These institutions of the memory formed by the galleries, the libraries, the archives and the museums (known in the Anglo-Saxon’s world as the GLAM –Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums–) pushed these big projects to expand the access to its collections (24 hours service, with massive sessions, etc.), transform the services offered and increase the preservation and conservation of the physical documents (creating some guidelines digitalization projects for part of the IFLA and the ICA.1 Even so, this development was somewhat stalled between the 2007 and 2008, with the economic crisis, when the human and material resources began to decrease.

Nonetheless, it is at this moment in time in which the movement open source and the social participation by means of the social networks stands out; no only in the field we are dealing with but at global level. Therefore, the contribution and the collaboration through the network between the big institutions, and also between these and their users, bring about projects like crowd sourcing. The TERMCAT (2012) translated crowd sourcing as a “supply participatory” and understands it as an open call in order to “cater of services, ideas or contents”.

The institutions of the memory also have taken part in these type of projects, with initiatives like the massive transcriptions, since they solved some limitations (cost and personal limitations); they improved the access to the collections and involved the users by creating communities.

2 Crowdsourcing or participatory supply

The term crowd sourcing appeared for the first time in 2006 in the magazine Wired through the writer Jeff Howe in his article The rise of crowd sourcing. The term groups two independent words: crowd (which refers to the crowd) and sourcing (that links it with the source) and defines it as the act in which an organization leases a function previously realised by the employees to a whole network of people, as an open challenge, in exchange for a reward.

Although the term appears at that moment, different actions that can be related were already identified before that moment. Pierre Lévy (1997) speaks of how the collective intelligence can surface in the world of the cyberspace; two years later, Tim Berners-Lee and Mark Fischetti (2000) suggest for the term “inter-creativity”, which looked for the creation of collective elements in the network. On the same line, Howard Rheingold (2003) spoke of the smart mobs or intelligent crowds as a social revolution.

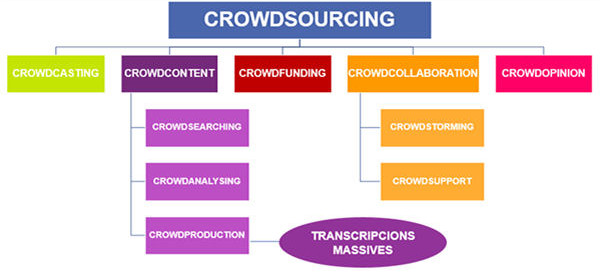

There exist different classifications of crowd sourcingbut one of the most consolidated, after realising different analyses, is the one proposed by Estellés-Arolas and González-Ladrón-de-Guevara (2012).

Figure 1. Classification of different types of crowdsourcing Source: Own, conducted based on Estellés-Arolas and González-Ladrón-de-Guevara (2012)

The authors distinguish between 5 big typologies depending on the type of task being realized. In the crowd casting, there is a call to solve a problem offering a reward to that who can solve it first or in the best possible way. On the other hand, in the crowd content people contribute their work and knowledge to create content. It is subdivided in crowd searching (massive search on Internet on a concrete subject), crowdanalysing (a variation of the previous where the search is done in multimedia documentation) and crowd production (creation of content in an individual or collective way. The projects of massive transcription are included here). In the crowd funding, funding is searched by means of small contributions and in the crowd opinion one tries to find out the opinion of the crowd on a specific subject or a new product. Finally, the crowd collaboration is identical to the crowd content except for the fact that there is no communication between the individuals and no reward offered. It is divided in crowd storming (brainstorming) and crowd support (solution of doubts).

2.1 Volunteering

The crowd sourcingprojects can’t be understood without the volunteering phenomenon. Caroline Haythornthwaite (2009) discerns two patterns differentiated not only in different projects but in a same. The patterns that she distinguishes are the “multitud” (crowd) and the “comunitat” (community). Concerning the first, there are shared experiences and the feeling of belonging is shorter, and can be linked to a single project (without any further expectations). Instead, the community shares values, experiences and objectives on a long-term basis; which will translate into a more effective call.

Thomas Knoll (2011) identified the differences between both patterns, as shown in the following table (table 1).

| Crowd | Community |

|---|---|

| Motivation for pride | Motivation for purposes |

| They feed on inspiration | Fed by the influence |

| They want profits | They want to belong |

| They need to feel connected | Promoted through collaboration |

| They need to get something | They like to bring |

| Are based on service | They are supported by history |

Table 1. Main differences between many communities as T. Knoll. (source: own)

3 The massive transcriptions

As mentioned previously, massive transcriptions are included in the category of crowd content or creation of content.

Massive transcription is understood as the action to write a text in another format as a simple representation of the same document or as data research to be entered into a database. Many of the projects of massive transcriptions are created with the aim to generate descriptive and textual information that can serve as a point of access to historical documents.

The projects of massive transcription can be divided depending on whether we apply the optical recognition of characters (OCR), by means of a specific software, or whether no such software is applied to them.

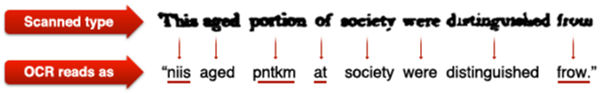

In the first case, the software identifies symbols or characters that form a specific alphabet and creates a text file with the data obtained. The volunteer will correct the orthographical errors that may happen due to the bad recognition of the characters (odd symbols, letters not recognized, etc.).

Figure 2. Example of application OCR correction of errors Proofreaders. Source: Lardinois (2008)

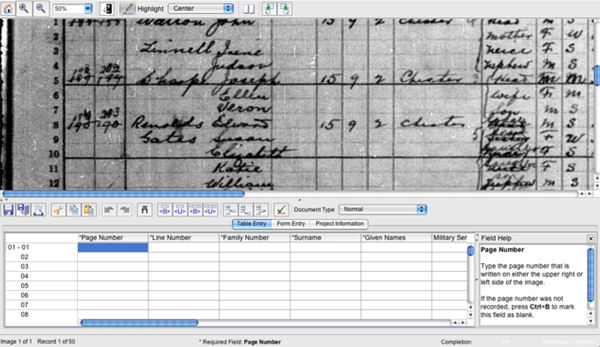

In the second case, the volunteer will have to transcribe the document from square one, since there is a whole range of documents that, to date, cannot yet be subject to the OCR, such as handwritten documents.

Figure 3. Example of transcription from zero to Familysearch Indexing

3.1 Workflow in the massive transcriptions

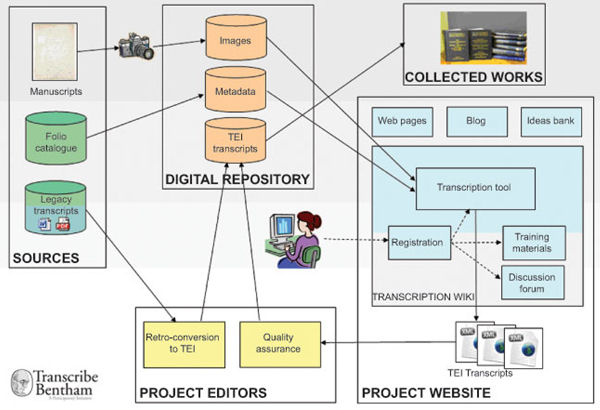

Many of the crowdsourcing projects follow the same workflow or map of processes. Before beginning, it is necessary that the manuscripts that need to be transcribed are digitalized and loaded into a file digital of the institution in order for people to have free access to the network.

The file digital has to allow the transcription of the documents and therefore, it is necessary to have a tool of transcription (that can be of free software or paying software). This tool will allow the volunteer to interact with the images to be transcribed and, once this process has been finalized, this same tool will export it to a format which can be read by the machine.

These metadata will be validated (or not) by the staff in charge of the project and will become part of the digital file, as a new element to enrich the searches.

Figure 4. Map of the processes carried out in a draft transcript massive. Source: Moyle, Tonra and Wallace (2011)

4 Analysis of massive transcription projects

In this part we show the analysis of 20 projects of massive transcription. Each of the 20 projects analyzed follows the same diagram: a short introduction to the project highlighting some significant elements and later, another analysis based on different indicators created from the guidelines proposed by Codina (2000) and Barrueco et. al. (2014) and others taking into account the specificities of the projects to analyze.

The selection of these 20 projects is based mainly on the fact that they are active projects and, therefore, allowed for checks in first person. In addition, we looked for an international dimension and for various themes within the massive transcriptions.

4.1 Projects

4.1.1 Distributed Proofreaders

In 2000 the project Distributed Proofreader (linked to the digital library Project Gutenberg) was born.2

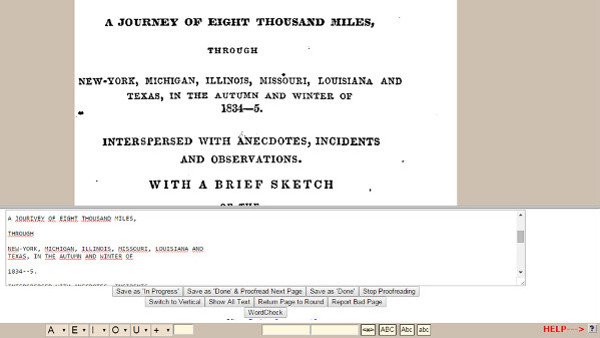

By means of a wiki platform and through a white box (see figure 5) the volunteers have to correct the digital texts that had been subjected to the OCR but not attained the level of quality wished.

Figure 5. Display the white box for the correction of texts Proofreaders

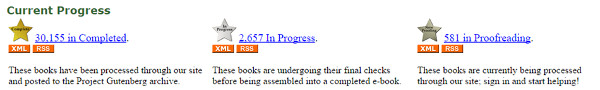

The initial screen shows the aims attained until the moment and those that want to be attained (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Show the progress of completed documents in progress and are being processed for Proofreading

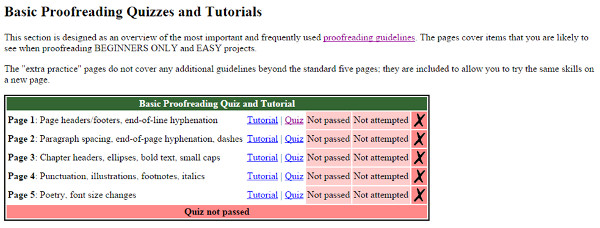

Another element worth highlighting is that it puts at the disposal of volunteers a whole range of guidelines to correct the documents and tutorials with evaluation tests to be done before initiating the transcription (see figure 7).

Figure 7. Tutorials and assessment tests to Proofreaders

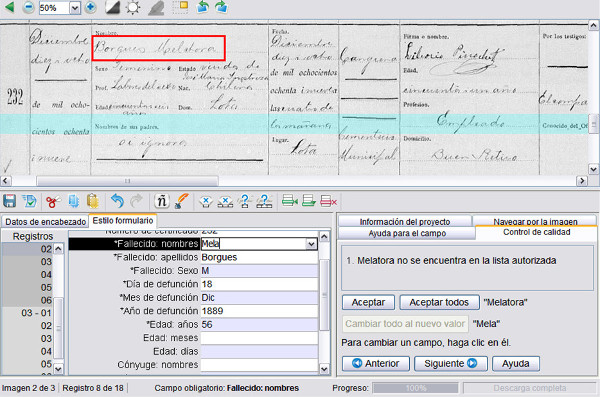

4.1.2 FamilySearch Indexing

In 2000 the FamilySearch Indexing is created to transcribe thousands of genealogical registers preserved and digitalized for The Genealogical Society of Utah.3

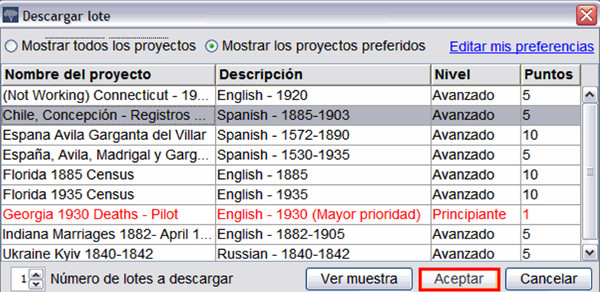

Through a software owned by the institution, we can install the package of transcription and begin to transcribe according to projects, language or level of the documents (see figure 8).

Figure 8. Panel selection lots Familysearch Indexing

The type of transcription is quite guided and with tools to support and train users. Once the document has been transcribed, the program applies a quick quality control to those transcriptions that appear to be a bit unclear (see figure 9).

Figure 9. Sample quality control in Familysearch Indexing

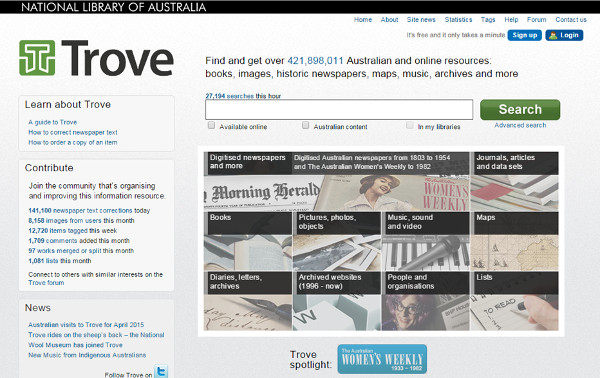

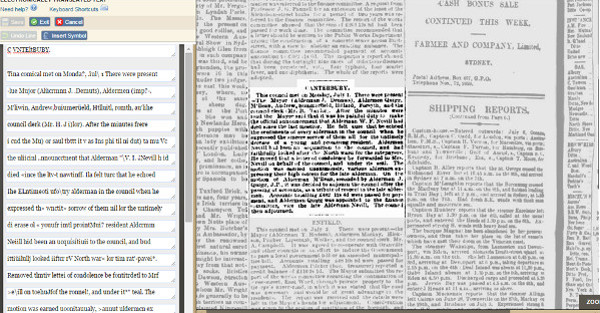

4.1.3 Australian Newspaper Digitization Program

In 2008, the National Library of Australia created the platform web Trove, with its own API, in order to correct the transcriptions resulting from the application of the OCR to the Australian press digitalized since the 1800.

The main screen of the project shows clearly the institution to which it belongs, what can be found and the different manners to contribute (see figure 10).

Figure 10. Main screen of project Australian Newspapers Digitalisation Program in Trove

The interface of correction shows the image digitalized and the text resulting from the OCR. Through a white box, the volunteer will have to correct all the typo errors (see figure 11).

Figure 11. Interface for proofreading in Australian Newspapers Digitisation Program

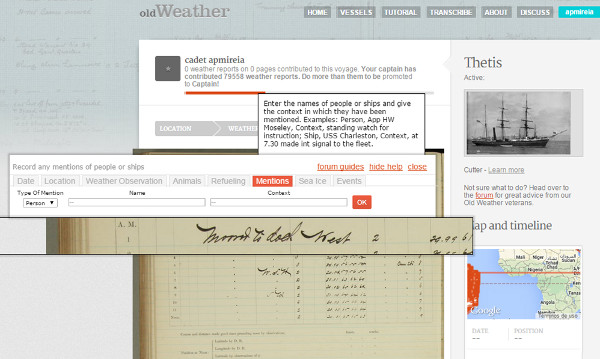

4.1.4 Old Weather

Project of digitalization and transcription of the inboard logs of different American ships of the 19th century that was launched in October of 2010 in the platform Zooniverse.4

In any one of the projects of the platform Zooniverse, before initiating the transcription, it is necessary to follow a short tutorial in order to get acquainted with the interface, the documentation, the type of transcription, etc.

The transcription is guided, since it shows us the page to transcribe and opens us a picture of dialogue with the different fields to transcribe (see figure 12).

Figure 12. Show transcription tour in Old Weather

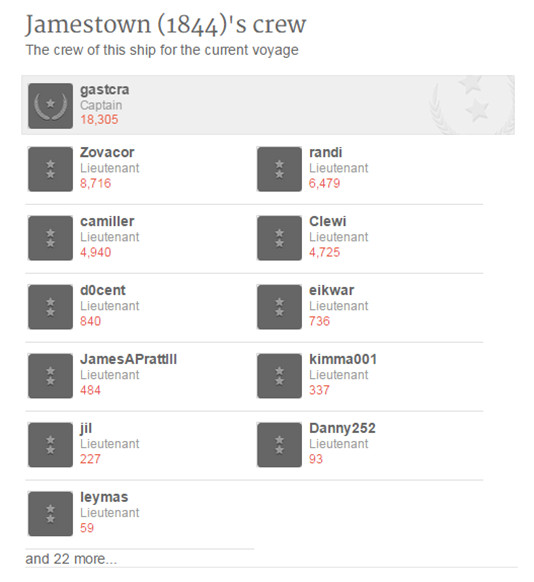

The registration of the voluntary is compulsory and this allows to consult the history of transcriptions, subscribe to newsletters, comment on the forums of the project and to award categories in function of the activity of each volunteer (see figure 13).

Figure 13. Sample of different categories according to documents transcribed Old Weather

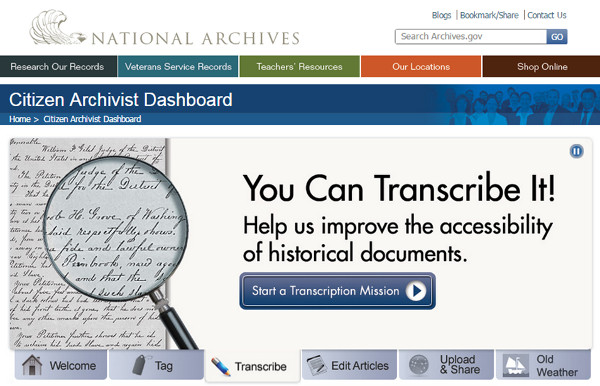

4.1.5 Citizen Archivist Dashboard

In 2011, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) of the USA created a platform web, with its own API, known as Citizen Archivist Dashboard which englobed different projects of crowdsourcing. The volunteers could label, transcribe or write new articles (see figure 14).

Figure 14. Slider Citizen Archivist Dashboard with different actions to perform

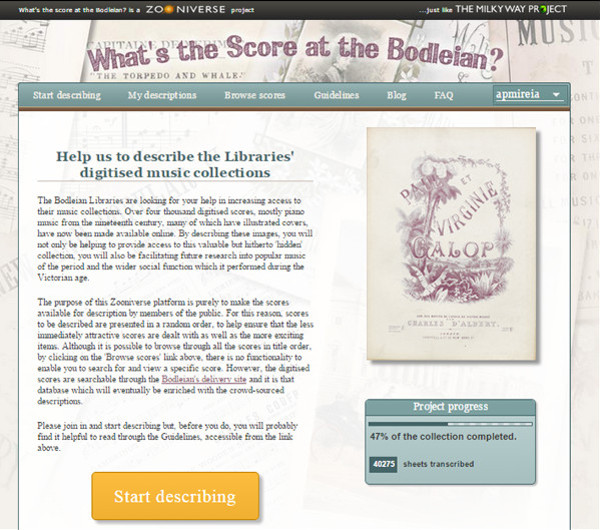

4.1.6 What’s the Score at the Bodleian?

In 2011, the Bodleian Library and Radcliffe Camera of the University of Oxford created this project cover by the platform Zooniverse. The aim was to transcribe more than 4.000 digital scores since the 1860.

The type of interface and transcription follows the same pattern that all the projects of Zooniverse. What’s worth highlighting is that in the main screen we see a progress bar showing the progress of the project (see figure 15).

Figure 15. Home screen of project What’s the Score at the Bodleian?

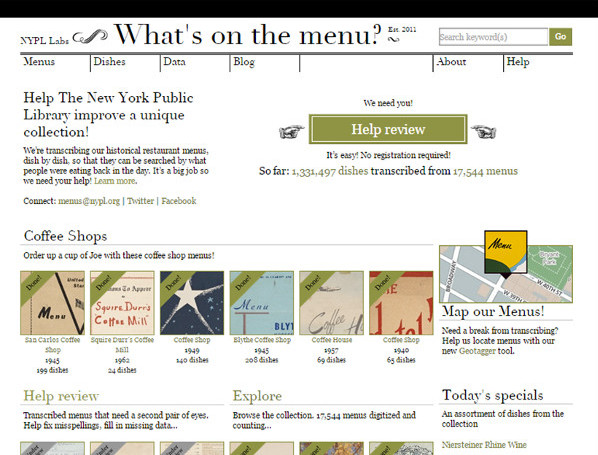

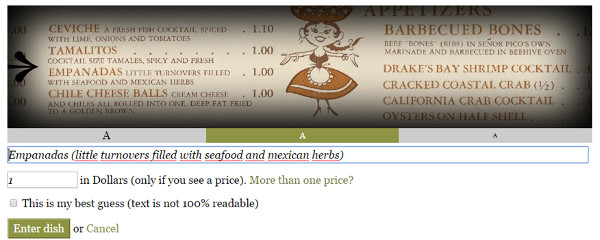

4.1.7 What’s on the Menu?

At the end of April 2011, the New York Public Library launched the project What’s on the Menu? In order to transcribe dishes and prices and geo-label more than 45.000 menu cards since the 1840s to date (see figure 16).

Figure 16. Home screen of project What’s on the Menu? at NYPL

The type of transcription is partially guided, since it offers a white box to transcribe the text but also allow to add the price in another field (see figure 17).

Figure 17. Show the transcription What’s on the Menu? at NYPL

It is particularly interesting to look at the “Today’s specials” section, which contains a daily selection of recipes transcribed to be shared on the social networks.

Figure 18. Show media through social networks dishes transcripts in What’s on the Menu?

4.1.8 Transcribe Bentham

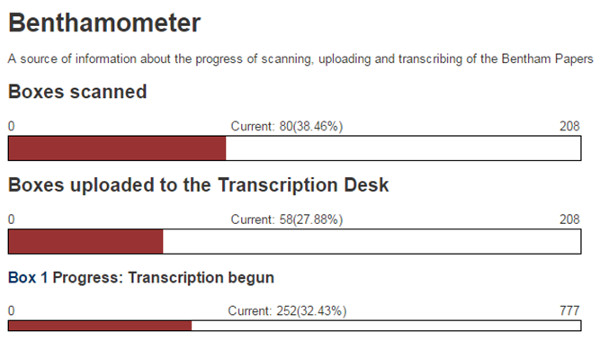

The University Collage of London together with other institutions created in 2010 this project to transcribe the handwritten documents by Jeremy Bentham, English philosopher and politician.

The platform to access the project is a wiki called Transcription Desk. Apart from the progress bar, we also find the Benthamometer, which shows the different phases that want to be achieved concerning the scanning, uploading into the platform and transcription (see figure 19).

Figure 19. Benthamometer, project status

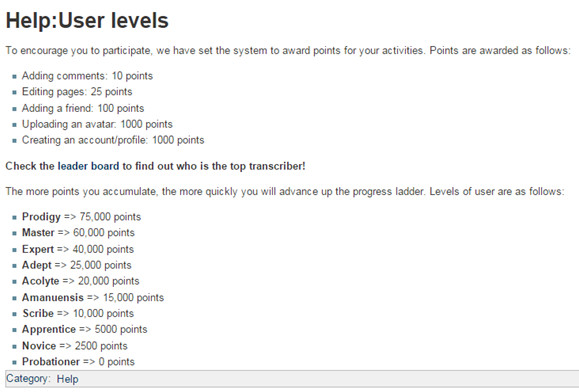

In this project the volunteers obtain points in relation to the tasks they realize and, in this way, they can escalate positions in the ranking of transcriptions (see figure 20).

Figure 20. Points associated tasks in Transcribed Bentham

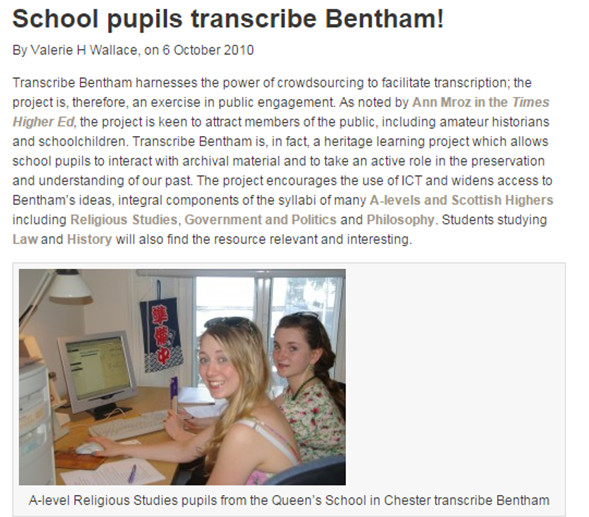

Another strong point of this project is the initiative of educational learning associated to it; that is to say, the students, of different levels of age, can learn by means of the research in the original historical manuscripts (see figure 21).

Figure 21. Page showing how students participating in the project Transcribed Bentham

4.1.9 DIY History

DIY History arises of the extension of the initial project of the University of Iowa Libraries which intended to transcribe the wartime newspapers for the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War.

The platform has been created with the free software Omeka and covers multiple collections to transcribe. It shows graphically the progress of the process (see figure 22).

Figure 22. Progress bar the collection of documents particularly DIY History

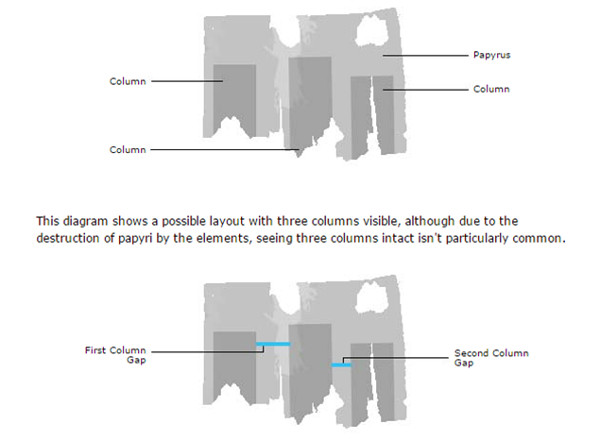

4.1.10 Ancient Lives

Ancient Lives forms part of Zooniverse and aims to transcribe thousands of Greek papyruses. Due to the inner characteristics of these documents, this project has very well developed transcription and platform guidelines (see figure 23).

Figure 23. Show how to determine measures on papyrus Ancient Lives

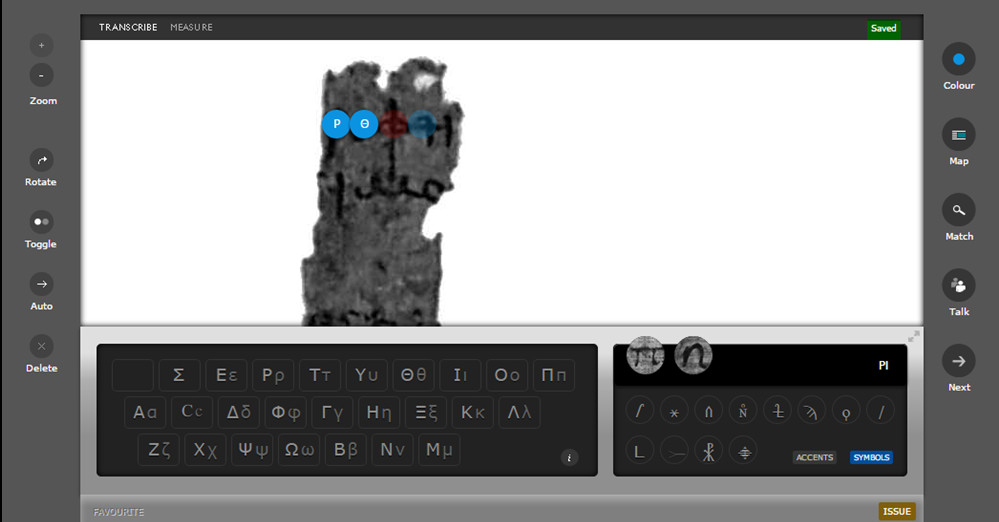

The type of transcription is also particular. It shows the papyrus to transcribe and also a keyboard with the different characters in order to select them directly (see figure 24).

Figure 24. View the transcript used in Ancient Lives

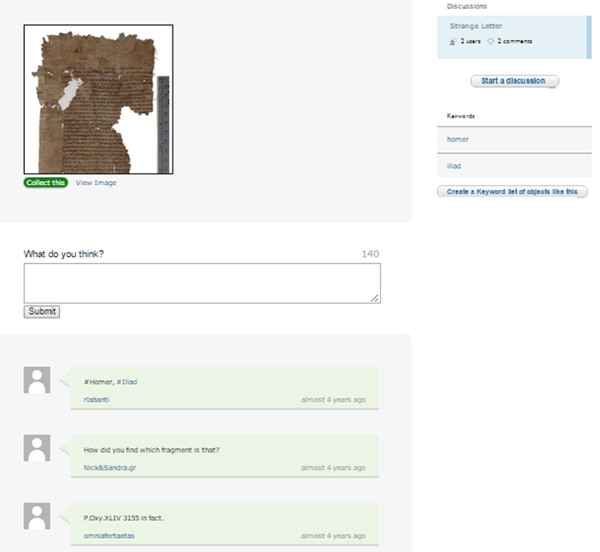

Also it highlights the part “Talk”, which works as a forum where the different volunteers can share their experiences or ask for advise and support (see figure 25).

Figure 25. Show “Talk” forum in Ancient Lives

4.1.11 Genealogy Vertical File Transcription Project

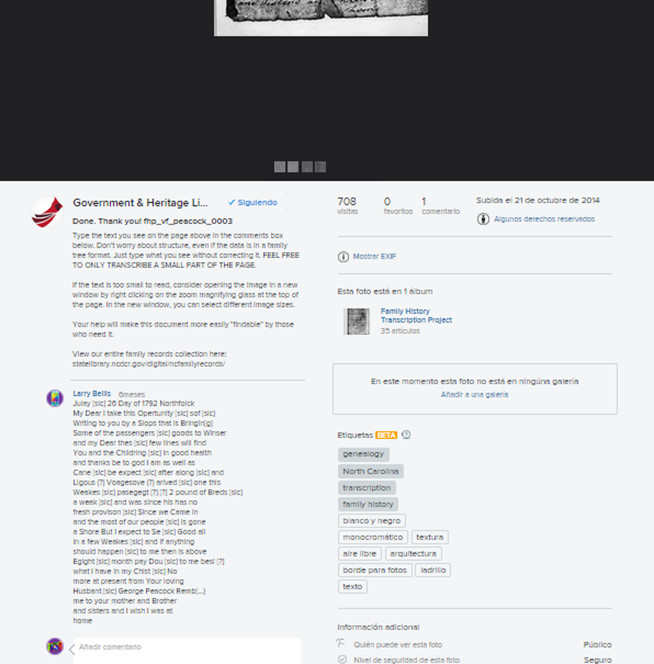

Initiative developed within the project North Carolina Family Records Online of the State Library and State Archives of North Carolina (USA), which intended to put at the public’s disposal different materials preserved by this institution.

What is special about this project is that it uses the social network Flickr. This platform shows the images to be transcribed and the volunteers only need to add a comment with the text transcribed (see figure 26).

Figure 26. View social network Flickr transcripts and comments by Vertical File Genealogy Transcription Project

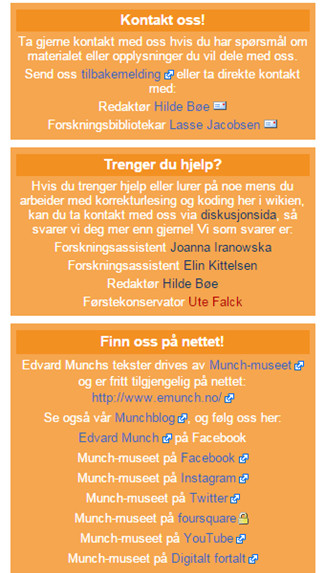

4.1.12 Edvuard Munch’s Writings

This project was created in 2011 to make available to the public around 13.000 pages of hand-written documents from the author.

The project resembles that of Transcribe Bentham, and received support from its creators. The communications channels are very well developed (see figure 27).

Figure 27. Sample of various communication channels to Edvard Munch’s Writings

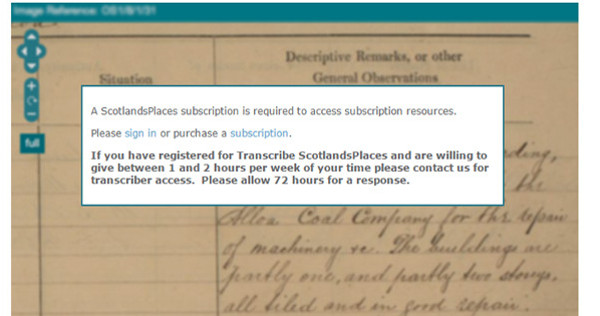

4.1.13 Transcribe ScotlandPlaces

In 2012, the web portal Transcribe ScoltlandPlaces was launched. The idea was to transcribe information out of more than 15.000 pages of historical documents, from 1645 to 1880, in order to locate places and historical figures in Scotland.

The volunteer needs to register and select the different collections in which he wants to participate. After 72 hours, the administrators grant them access to the transcriptions (see figure 28). This may increase controls but may also make us loose volunteers.

Figure 28. Sample message waiting 72 hours to start transcribing

4.1.14 The arcHIVE

The National Archives of Australia within the National Archives’ labs environment

Figure 29. Sample of different search possibilities The arcHIVE

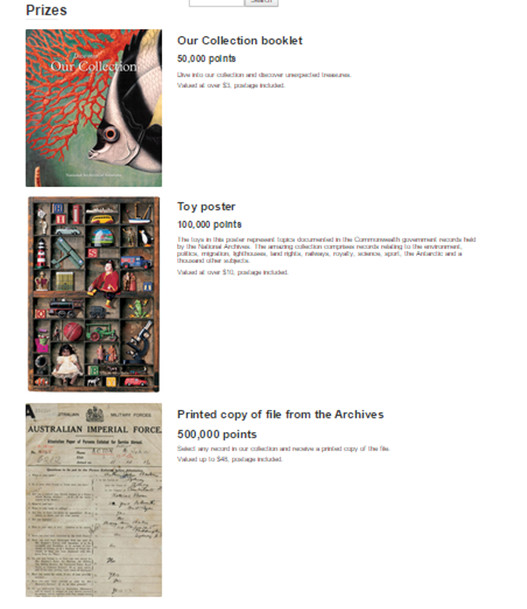

Figure 30. Rewards in The arcHIVE

4.1.15 Smithsonian Digital Volunteer: Transcription Center

In July 2013, the Transcription Center of the Smithsonian Digital Volunteer was launched. The project wanted to transcribe thousands of documents from some 30 collections of different museums, files and libraries of the Smithsonian Institution.6

In order to select the document to transcribe, a code of colours is displayed (green, yellow and red) depending on the state of the document and of the task the volunteer wants to achieve (see figure 31).

Figure 31. State of progress of the document in Smithsonian

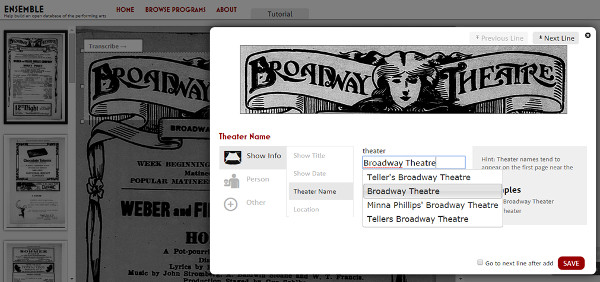

4.1.16 Ensemble

The New York Public Public Library for the Performing Arts initiated in 2013 this project to transcribe different elements (name of the theatre, location, title, characters, etc.) which appear in the programs of theatre, dance or concerts.

We highlight from this project the type of guided transcription. With the document to be transcribed in screen, it is necessary to select the different elements to transcribe and, once selected, it is necessary to indicate the field that would need to be filled (see figure 32). Besides, once selected, the field offers us a list of authorities for greater quality control.

Figure 32. Show transcription tour in Ensemble

4.1.17 Transcriu-me!

In 2013, the Library of Catalonia with the Consortium of University Services of Catalonia started the project Transcriu-me!! in order to improve the access to its documentation. Later, other institutions, such as the Filmoteca of Catalonia or the University of Barcelona, also added to the project.

The transcription is done by means of a white box and shows the description norms in the same screen (see figure 33).

Figure 33. Type of transcription and guidelines in Transcriu-me!!

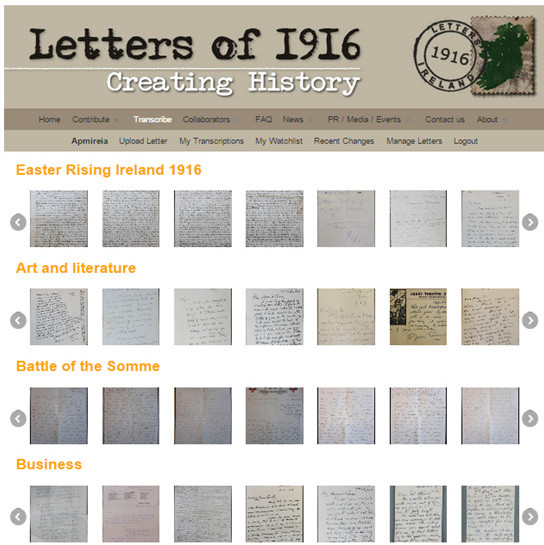

4.1.18 Letters of 1916

Project initiated in 2013 by different institutions of Ireland for collect and transcribe letters from the Easter Rising period.7

The documents to transcribe are shown in different collections ordered by theme, without determining the percentage of documents transcribed or the level of difficulty (see figure 34).

Figure 34. Shows the collections in Letters of 1916

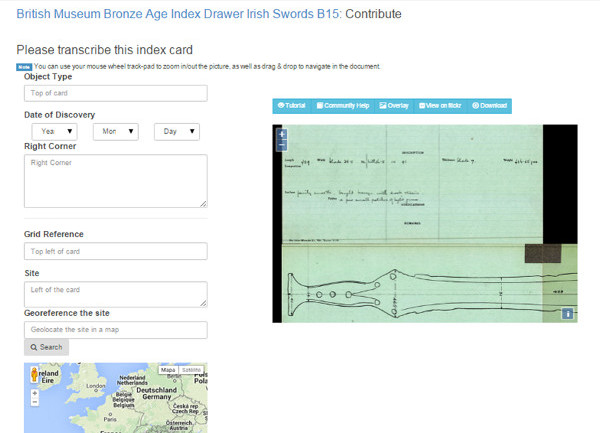

4.1.19 MicroPasts: Crowdsourcing

In October 2013, the project MicroPasts was launched by the British Library, the University College of Londonand the Arts and Research Council. Through a free platform and an open source (Pybossa), it wanted to collect as much quality data as possible on different thematic such as archaeology, history or heritage.

The type of transcription is guided, since it is necessary to transcribe the document in different fields. Thanks to Flickr the image can be seen at very high resolution, and the works can be located through a Google map (see figure 35).

Figure 35. Transcription guided in MicroPast

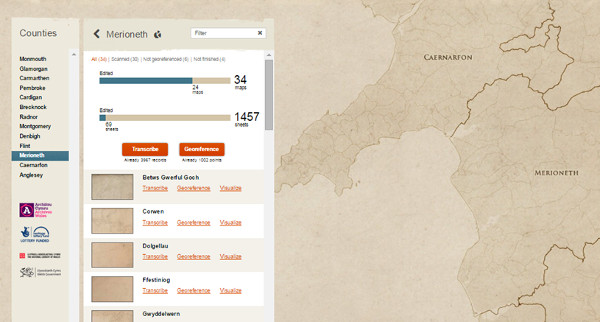

4.1.20 Cynefin: Mapping Wales’ sense of Place

This project was launched in 2014 in order to collect relevant information on the localization of the whales in the United Kingdom.

To select a document, a map appears and the volunteer can choose the country zone where he wants to transcribe and locate the documents (see figure 36).

Figure 36. Sample of documents transcribed in a collection Cynefin

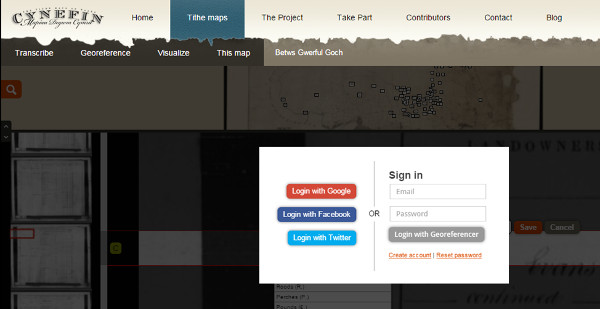

We highlight the fact that to speed up the process, the volunteer can use any one of the main social networks (see figure 37).

Figure 37. Sample the variety of ways to register Cynefin

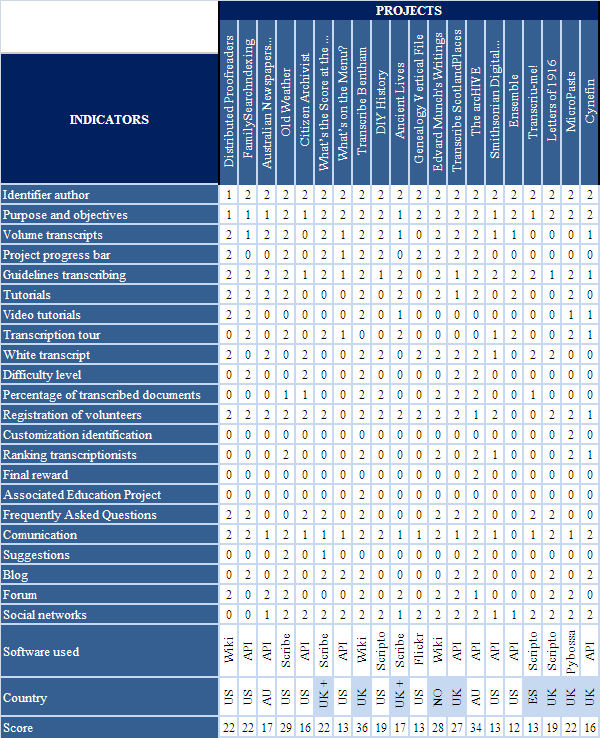

4.1.21 Summary table

We show now a summary of the different projects with the resulting score for each indicator.

Table 2. Summary table of projects analyzed

In summary, we can see that some indicators are common to all projects, such as: the identification of the author who realizes the project, as well as the aims pursued, the inclusion of transcription guidelines, and the registration of volunteers in order to take part in the process. Finally, the use of the social networks is basic to promote the project.

On the other hand, there are three big groups which can be differentiated depending on the degree of performance of the indicators studied. Bearing in mind that the maximum score that each project could attain was of 44 points, we find in the highest positions, (with a score of 36 and 34, respectively) the projects Transcribe Bentham and The arcHIVE. Following close, we find: Old Weather (with 29 points), Edvard Munch’s Writing (with 28 points) and Transcribe ScotlandPlaces (with 27 points). And, finally, the rest of projects obtain an equal or lesser score of 22 points.

Therefore, we can conclude that many projects of massive transcription are being undertaken at international level, but only a few of those are really standard-setting projects.

5 Best practices in projects of massive transcription

Bearing in mind the summary of the different projects analyzed, we can determine a set of best practices to be applied when designing a project of massive transcription.

- Description of the project, how it originates, to which institution it belongs and what it pretends to achieve. Giving out all this information gives the volunteer confidence and allows him to have a clear idea of what his contribution can really mean to the project.

- Bar showing the progress of the process. It is an element which technically does not suppose any type of complication nor effort to the institution and can help undecisive volunteer to decide whether to take part or not in the project.

- Transcription guidelines, user guides and video tutorials to understand and adapt to the context. Providing transcription guidelines can help the volunteer solve potential doubts in his contributions. At the same time, reviewing a learning guide or watching a video tutorial is always more grateful than having to read two pages on how to transcribe the documents.

- Easy and simple utilization of the tool to transcribe. Using a simple interface will ensure there is no digital gap for the novel volunteer and will give everyone the same level of opportunity.

- Favour a guided transcription and determine the level of difficulty of each document. It is necessary to favour the guided transcription in the white box, as that will help the volunteer to perform the task better and quicker. Besides, the classification of the documents depending on the level of difficulty will allow the beginners to start transcribing the documents which are more adapted to their level.

- Identification of the volunteer to personalize the experience. It will increase the commitment to the voluntary if his work is registered and s/he can see the evolution of the work he is doing.

- Participation rankings and final reward. It is about rewarding volunteers for the loyalty and reward their dedication to the transcription of documents.

- Linking the transcriptions to educational projects. It is necessary to link these type of projects to other more educational projects in order to understand the history and our heritage in a more personal way.

- Use of the social networks, the forums and the blogs to keep the communication with the volunteers. This is key to ensure the loyalty of users, and ensure they can share what they do. This can help attract new users.

Bibliography

Barrueco Cruz, J. et al. (2014). Guía para la evaluación de repositorios institucionales de investigación [en línia]. 2a ed. Recolecta, FECYT–CRUE–REBIUN <http://recolecta.fecyt.es/sites/default/files/contenido/documentos/GuiaEvaluacionRecolecta_v.ok_0.pdf>. [Consulta: 21 maig 2015].

Berners-Lee, T.; Fischetti, M. (2000). Tejiendo la red: el inventor del world wide web nos descubre su origen. Madrid: Siglo XXI de España editores. ISBN 8432310409.

Codina, L. (2000). Evaluación de recursos digitales en línea: conceptos, indicadores y métodos. Revista española de documentación científica [en línia]. <http://redc.revistas.csic.es/index.php/redc/article/viewFile/315/479>. [Consulta: 5 maig 2015].

Estellés-Arolas, E.; González-Ladrón-de-Guevara, F. (2012). “Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition”. Journal of Information Science, vol. 38, no. 2, p. 189–200. <http://www.crowdsourcing-blog.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Towards-an-integrated-crowdsourcing-definition-Estell%C3%A9s-Gonz%C3%A1lez.pdf>. [Consulta: 10 gener 2015].

Haythornthwaite, C. (2009). “Crowds and communities: Light and heavyweight models of peer production”. System Sciences, 2009. HICSS’09. 42nd Hawaii International Conference on. IEEE. p. 1–10.

Howe, J. (2006). “The Rise of Crowdsourcing”. Wired magazine, no. 14.06. <http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html>. [Consulta: 10 gener 2015].

Knoll, T. (2011). “Are Your Customers a Crowd or a Community? “. SXSW Interactive 2011. <http://lanyrd.com/2011/sxsw/scqyt/>. [Consulta: 23 maig 2015].

Lévy, P. (1997). Collective intelligence: Mankind’s Emerging World in Cyberspace. New York and London: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-45635-0.

Rheingold, H. (2003). Smart mobs. De Boeck Supérieur, vol. 1, p. 75–87. ISSN 0765-3697. <http://www.cairn.info/resume.php?ID_ARTICLE=SOC_079_0075>. [Consulta: 5 maig 2015].

TERMCAT (2012). Crowdsourcing en català [en línia]. Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Cultura <http://www.termcat.cat/ca/Comentaris_Terminologics/Finestra_Neologica/142/>. [Consulta: 30 maig 2015].

Notes

* This article is originally a Final Project for Information and Documentation of the School of Library and Information Science from the University of Barcelona, argued in July 2015 under the tutorship of Ciro Llueca and Fonollosa.

1 Directrius per a projectes de digitalització de col·leccions i fons de domini públic, en especial els de biblioteques i arxius (2006) [on line]. Barcelona: Col·legi Oficial de Bibliotecaris-Documentalistes de Catalunya. ISBN 8486972221. <http://www.cobdc.org/publica/directrius/sumaris.html>. [Accessed: 20 may 2015].

2 Nonprofit institution founded in 1971 by Michal S. Hart. The aim is to create a digital library full texts of public domain world’s largest and maintained through the efforts of volunteers and microfinance.

3 Society closely linked the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, known as the Mormon Church.

4 Zooniverse is a citizen science web portal created and maintained by Citizen Science Alliance. The different partners of this alliance are: Adler Planetarium (USA), Johns Hopkins University (USA), University of Minnesota (USA), National Maritime Museum (UK), University of Nottingham (UK), Oxford University (UK) and Vizzuality. The main objective is to create projects that can promote crowdsourcing subsequent scientific research in various disciplines such good: astronomy, ecology, cell biology, humanities or the weather. The original project was on Galaxy Zoo volunteers galaxies classified according to their characteristics. According to the 2014 community Zooniverse had surpassed one million registered users and had promoted more than 70 scientific articles.

5 Lab environments referring to the National Archives of Australia. To improve access to the collection created several prototypes that can develop production services and can remain in a state pilot.

6 Institution funded by the US Government which aims to increase and diffusion of knowledge. Consists of 19 museums in different areas (artistic, historical or zoos, etc.) and research centers (archives, libraries and research institutes).

7 Easter Rising, also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an uprising that took place the military council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (Irish Republican) during Easter 1916 to end British rule and separate from the UK.

Creative Commons licence (

Creative Commons licence (