Anne van den Dool

Redactora, autora i periodista

Abstract

The originally Danish principle of The Human Library has been known in the Netherlands for about six years now. Even during the coronavirus crisis, the organizers managed to reach more than 700 people in over 20 sessions. The high average rating given by the participants is in line with the positive results of previous studies on the impact of The Human Library. A distinction can be made between short-term and long-term effects, effects on voluntary participants versus participants in an edition of The Human Library in a mandatory setting, such as a work situation, and effects achieved in terms of awareness, change in attitude and behavioural change. In almost all of these areas, The Human Library scores high. In the future, more research can be done into the distinction between these different situations, as well as on the effect on the ‘books’ rather than the ‘readers’, on whom almost all research now focuses.

Resum

El concepte originàriament danès de la Biblioteca Humana es coneix als Països Baixos des de fa uns sis anys. Fins i tot durant la crisi del coronavirus, els organitzadors van aconseguir arribar a més de 700 persones en més de 20 sessions. L’alta qualificació mitjana donada pels participants està en consonància amb els resultats positius dels estudis previs sobre l’impacte de la Biblioteca Humana. Es pot fer una distinció entre els efectes a curt i llarg termini, els efectes en els participants voluntaris davant dels que participen en una edició de la Biblioteca Humana en un context obligatori, com una situació laboral, i els efectes aconseguits en termes de conscienciació, canvi d’actitud i canvi de comportament. En gairebé totes aquestes àrees, la Biblioteca Humana obté una puntuació alta. En el futur, es pot investigar més sobre la distinció entre aquestes diferents situacions, i també sobre l’efecte en els “llibres” en lloc dels “lectors”, en els quals gairebé tota la investigació se centra ara.

Resumen

El concepto originalmente danés de la Biblioteca Humana se conoce en los Países Bajos desde hace unos seis años. Incluso durante la crisis del coronavirus, los organizadores lograron llegar a más de 700 personas en más de 20 sesiones. La alta calificación promedio dada por los participantes está en consonancia con los resultados positivos de estudios previos sobre el impacto de la Biblioteca Humana. Se puede hacer una distinción entre los efectos a corto y largo plazo, los efectos en los participantes voluntarios frente a aquellos que participan en una edición de la Biblioteca Humana en un contexto obligatorio, como una situación laboral, y los efectos logrados en términos de concienciación, cambio de actitud y cambio de comportamiento. En casi todas estas áreas, la Biblioteca Humana obtiene una puntuación alta. En el futuro, se puede investigar más sobre la distinción entre estas diferentes situaciones, así como sobre el efecto en los “libros” en lugar de en los “lectores”, en quienes casi toda la investigación se centra ahora.

1 Introduction

I remember the first time I came into contact with The Human Library. About three years ago, shortly before I was to find my first job in the library sector, I was walking through the city centre of my home town and decided on a whim to re-enter the central branch of the public library. Inside, I did not find the usual silence of mothers with children scurrying about, students working diligently and staff members silently putting books back — no, this time the place was bustling with activity. Tables were spread around the room, each with two people at it, who all seemed to be engaged in animated conversation. Around them stood interested parties, who listened with keen ears to their stories.

The busiest place was at the counter near the entrance: a raised table behind which stood a young woman, pointing to a board. On the board were two columns: one category ‘loaned’ and one category ‘available’. At the request of those who came to her desk, she moved the magnetic placards on the board from one column to the other. The placards read words such as ‘Homeless’ and ‘Transgender’.

When I asked what was going on here today, she explained that I had stepped into the middle of a Human Library. Today, not only were books lent out, but also people, she said: at the tables were people who wanted to share their life stories with others, and people who were interested in those stories. I was allowed to sit at a table too, if I wanted to. One of the human books, as she called them, was still free.

I took a seat opposite a person whom I would at first have thought was a man, who introduced herself as Sylvia. It was then that I noticed the earrings, the dress, the lipstick. What followed over the next twenty minutes was a frank conversation in which I learned that men were not allowed to walk the streets dressed as women until the 1980s, the difficulties this Sylvia had had to face in order to be allowed to wear a skirt on the shop floor, and the psychological difficulties that can arise when you cannot be who you are.

My human book was not the only one in the room with a touching story, as I understood as I walked through the library after the talk. The other tables included a former member of an Islamic movement in Egypt, a rape victim and a severely disabled woman. As I walked past the tables again, I also caught snippets of their stories. A young woman told how she suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after being assaulted on a date in her own home, after which she decided to start a debate on sexual violence in the Netherlands. The blog she wrote landed her on one of the biggest talk shows in the Netherlands, thus unleashing one of the biggest actions against sexual violence in twenty years. The Egyptian refugee has since created theatre performances about his own story of escape, and the woman with a congenital growth disorder was the chairperson of the interest group for small people.

In short, all their stories had a turning point in which they had transformed what had happened to them for the better. During that afternoon, they dared to be vulnerable about their past, but were just as proud of the steps they had taken to reclaim their lives. The fact that they were able to tell their story confidently to themselves and their interlocutors made it clear that they seemed to have succeeded.

2 Frequency and evaluation

By now, I know that the human library into which I stumbled that afternoon is by no means the only one in the world. In the Netherlands, across 24 meetings last year, a total of 720 conversations were held in the context of The Human Library, including adopted children, ex-convicts, asylum seekers, and drag queens. The locations were spread all over the country: from Groningen in the north to Vlissingen in the south, from the capital Amsterdam in the west to Tilburg in the east. Some of these meetings took place online, due to the measures taken regarding the coronavirus crisis.

Other visitors were just as impressed with The Human Library as I was: in the evaluation, 100% of the almost 450 respondents said they would recommend a visit to someone else. They appreciated the openness and lack of judgement in the conversations they had with total strangers, they said, and had also learned to look more closely at their own qualities and shortcomings through the activity. Of all respondents, 97% said they had gained new knowledge; the same percentage said they had gained a better understanding of the situation of the living book. On average, the respondents scored their visit 9.0 (The Human Library, 2021).

3 History and objectives

Dutch editions of The Human Library have been organized for about six years now; the first edition took place in 2014, in the Groninger Forum. Since 2017, Human Libraries have also been organized in other cities. However, the origin of the concept lies in Copenhagen. At the Danish festival Roskilde, the first edition was organized in 2000, then called ‘Menneskebiblioteket’, with a group of young people as initiators. One had been stabbed on an outing in 1993 and had decided to share his story with the world. The event was open for eight hours a day over four days and featured over fifty different titles. More than a thousand readers took advantage of it. Now, 21 years later, editions of the event have taken place in 85 countries, spread across six continents (The Human Library, 2019).

During those 21 years, several rules have been developed to help the event run as smoothly as possible. For example, books and readers should be treated with respect. Both parties have the right to ask any question, but they do not have to answer it. The conversation may also be ended by either party at any time. For the sake of completeness, the rules also state that the ‘books’ may not be taken outside. The metaphor of the book is consistently implemented in the house rules: readers must return the book in the same mental and physical state as they received it, and thus do not have the right to fold or damage the pages.

Only registered readers, who accept the rights of the book, can borrow books. The human books cannot be reserved: when the book of one’s choice is borrowed, one can read another book in the meantime. Two readers can borrow the same book if they know each other and if the book agrees. If the book in question is not available in a language the reader understands, they can ask for a dictionary in the form of a translator. Readers under the age of fourteen need parental consent or must be accompanied by a parent or guardian.

It is hoped that by observing these rules, space will be created to pursue The Human Library’s highest goal: creating space for dialogue and understanding. It is also about promoting respect for human rights and sharing the experiences of people who face stereotyping, prejudice, stigmatization, exclusion, and discrimination. In this way, visitors will hopefully develop an attitude of openness and acceptance towards people who are ‘different’, become aware of their prejudices and hopefully manage to put them aside. The Human Library is therefore emphatically not intended as an encounter with an exotic figure (The Human Library, 2021).

4 Impact research in the Netherlands

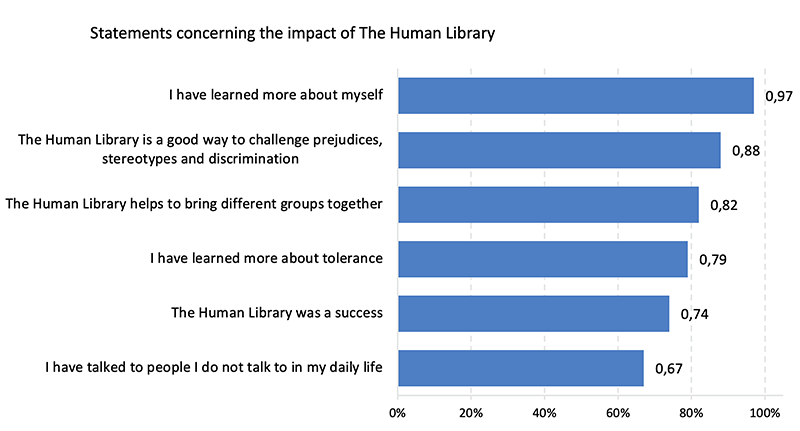

An initial study of the effects of The Human Library was conducted in 2015 by Karolin Jambor of the Hanze University of Applied Sciences in Groningen. She interviewed 103 participants in the Groningen edition of The Human Library in 2015, shortly after the first edition in the same city in 2014. Unlike many other studies, she interviewed both ‘books’ and ‘readers’. Many books described The Human Library as a very challenging but satisfying experience. Almost three quarters of all respondents rated the event a success. 82% of the respondents agreed that The Human Library, as a concept, helps to bring different social and ethnic groups together. Moreover, 67% of the respondents stated that they had talked to people they do not talk to in their everyday lives. 88% of the respondents agreed with the statement that The Human Library is a good way to challenge prejudices, stereotypes, and discrimination. The survey also showed that 47% of the respondents had gained new insights. Also, 97% of all respondents stated that they had learned something, or a lot, about themselves, and 79% felt that they had learned more about tolerance. The percentages in terms of attitude change were lower: only 52% stated that their attitude had changed to some extent, while 30% of all respondents felt that their attitude had changed completely (Jambor, 2015).

Figure. Statements concerning the impact of The Human Library. Source: Jambor, 2015.

In late 2017, psychologist Anna Handke conducted the first comprehensive study into the impact of The Human Library on the attitude of the participants. The study specifically addressed the question of whether visitors’ conceptions of the minority group with whom they had contact had changed for the better after the encounter. Eighty-seven visitors to an edition of The Human Library in Groningen in June of that year were interviewed at three points in time: before the event, immediately after the event and one month after the event.

The study proved to be a powerful support for the ultimate goal of The Human Library. Even a short conversation in which people voluntarily participate can be sufficient to improve the visitors’ attitude towards the minority group, the study showed. In doing so, the study was in line with earlier social psychological research that shows that the key to improving the attitude of one group towards another is contact between the two groups (Allport, 1954).

The Human Library indeed proved to have this effect: the attitude of the interviewees towards the spoken minority group was more positive after the interview than before. The quality of the interview transpired to be more important than the typicality, i.e., the extent to which the member of the minority group is representative of the group to which he or she belongs. However, visitors’ knowledge of the minority group increased, and fear of the group decreased. Handke observed no changes in empathy for this group. She concludes that The Human Library can already cause significant attitude changes within a short period of time, although not in all areas (Handke, 2017).

5 Foreign impact research

Impact studies into the effect of The Human Library have also been conducted outside the Netherlands. In 2020, the Danish research bureau Analyse & Tal was commissioned by the Zurich Foundation to carry out a qualitative study on the subject. The study was based on three virtual events organized by The Human Library in September 2020 for two hundred employees of the Zurich Insurance Group from different regions of the world. Some of the participants were interviewed prior to the events and three months afterwards.

This impact study shows that The Human Library helps visitors to gain a broader view of diversity and allows them to realize that an inclusive society can only come about if all parties are actively committed to change. The findings of these researchers, like the evaluations of The Human Library Netherlands and Handke’s research, show a high level of satisfaction and a significant short-term effect among participants. Interviews with the participants show that they can vividly remember specific details of the event. They also indicated that, in the months after the event, they had recurring thoughts about their experiences and reviewed their own prejudices on several occasions. They realized that diversity can take on more forms than just someone’s physical appearance. During the interviews, several respondents also indicated that attending the event had led to a change in behaviour. This raises the possibility that the effects of The Human Library may extend beyond the people who visited one of the editions: a change in behaviour may also positively affect others. Moreover, this study shows that implementation of The Human Library on the shop floor can also have a significant impact.

Research from Hong Kong in 2020 shows even broader applicability of The Human Library. There, research was conducted into this intervention as a key to the successful social inclusion of people recovering from mental illness, where mutual understanding is of great importance. This intervention was used to promote this form of social inclusion. Reports from mental health workers regarding their experiences showed that the Human Library is well-suited to facilitating social inclusion and promoting mental health recovery (Kwan, 2020). The difference in effects is particularly large when compared to large-scale, one-way intervention approaches. However, a clinical practice manual should be developed to inform future practitioners about the value of the Human Library approach in mental healthcare.

6 Conclusion and suggestions for follow-up research

The above-mentioned studies are, without exception, in The Human Library’s favour: in many cases, a visit is not only a positive experience, but it even brings about a change in attitude. No major differences between Dutch and foreign impact research can be observed in this regard. However, the above overview shows that, although several studies have been published on the impact of The Human Library in the short- and medium-term, a longer-term monitoring process has not yet been carried out. Furthermore, these studies mainly focus on the effects on the ideas and attitudes of the ‘readers’, and to a lesser extent on those of the ‘books’. Although an event usually reaches more ‘readers’ than ‘books’, studies that have examined the impact of The Human Library on the living book show that the effects among this group are not insignificant either. These effects are not necessarily directly linked to the goals set by the organization, but they can certainly influence the way these people relate to other groups after the event, even if they are a majority group.

References

Allport, G.W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Analyse & Tal (2021). Study on the Impact of The Human Library. Forthcoming.

Handke, A.L. (2017). “Don’t Judge a Book by Its Cover. Impact Evaluation of a Human Library”. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (RUG). <https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a2f3fe5bff2003632bd79e0/t/5a53c72a9140b7212c37535b/1515439920823/MAThesis_2015-2017_HandkeAL2+2.0.pdf>. [Accessed: 09/15/2021].

Jambor, K. (2015). “Human Library Evaluation Study. An Evaluation Study on the Objectives and Effectiveness of the Human Library”. Groningen: Hanzehogeschool Groningen. <https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a2f3fe5bff2003632bd79e0/t/5a52da0224a694bca85d4f1e/1515379207060/Human+Library+Groningen+2015+Evaluation+Study.pdf>. [Accessed: 09/15/2021].

Kwan, C. K. (2020). “A Qualitative Inquiry into the Human Library Approach: Facilitating Social Inclusion and Promoting Recovery”. In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 9, p. 3029. <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7246815/pdf/ijerph-17-03029.pdf>. <https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093029>. [Accessed: 09/15/2021].

The Human Library (2019). “About the Human Library”. <https://humanlibrary.org/about/>. [Accessed: 09/15/2021].

The Human Library (2021). “Jaarverslag 2020”. <https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a2f3fe5bff2003632bd79e0/t/5fedda82f218a25ea6fbd150/1609423495459/HL+2020+jaarverslag.pdf>. [Accesed: 09/15/2021].

Creative Commons licence (

Creative Commons licence (